Babelscope

“Computer science is no more about telescopes than astronomy is about computers” – Bizzaro Dijkstra

Introduction

I’ve had this idea for the past twenty years. What would happen if you had a computer and gave it random machine code? Obviously we’re not talking about anything with a BIOS or other low-level firmware; what would happen if you filled a Nintendo cartridge with random data, or mashed random bytes into the hex editor of an Apple II.

A few months ago, I made the Finite Atari Machine, a framework that did just that for the Atari 2600. I generated 30 billion different ROMs full of random data and emulated the ones that looked like commercial ROMs. The results were interesting: I found programs that generated cool, glitchy visuals and even a ‘protogame’ that responded to user input.

This experiment had significant shortcomings. Instead of emulating 30 billion ROMs, I used some heuristic filtering to single out the ROMs that could be games. The halting problem is a harsh mistress, and to find interesting algorithms in random data, you actually had to run billions of these random ROMs.

It’s the computer science equivalent of the Miller-Urey experiment. This was an experiment in chemical synthesis by simulating the primordial Earth in a test tube. Add water, methane, ammonia, hydrogen, heat and electric sparks and you’ll eventually get amino acids, the building blocks of life. I’m doing this with computer code. If you have a computer run random data as code, eventually you’ll get algorithms that do something.

Comparison to Related Works

The Babelscope is not without historical precedent, although it is by necessity a little bit cruder than other related work.

The closest thing to Babelscope is stoke from the Stanford Programming Languages Group. This uses random search to explore program transformations, but not a program space. It’s a bounded search, looking for novel or interesting permutations of interesting algorithms, but it’s not really for discovering algorithms in random data. Although, I’m using Babelscope to find sorting algorithms, so the comparison between it an Stoke is really six of one, half a dozen of the other.

A forerunner to stoke is the Superoptimizer. This ancient CS paper – nearly half as old as what I expect the audience of this post to be – used random perturbations to find the shortest program that would compute a given function. This is somewhat like what I’m doing, except the Babelscope looks at a huge search space to find any program that does something.

In literature, there are a few analogs to what I’m doing here. Borges’ The Library of Babel is the most obvious and where this project steals its name. It’s a short story, just go read it now, but the basic premise is that the universe is a library filled with random books. There’s a cult searching for the library index, and another cult destroying books that don’t make sense. Just go read it.

There’s also Victor Pelevin’s iPhuck 10, Russian fiction that cannot be easily translated into English because the main character is an LLM trained on the entire corpus of Russian literature. The summaries and commentary around this work talk about “Random Code Programming”, exactly what I’m doing here. iPhuck 10 uses quantum computers but the idea is the same – look at the space of random programs and see what pops out. I’d like to mention that I have not read iPhuck 10 because I can’t; I don’t speak Russian and I’m certainly not well-versed in Russian literature. But I like Star Trek VI because it’s a Shakespearean space opera and Wrath of Kahn because it was written by Melville, so I’d be interested in a translation.

Technical Background and Reasoning

While the Finite Atari Machine showed it was possible to find interesting objects in the enormous space of random programs, this technique had drawbacks. I was limited by heuristics, and there are trivial counterexamples for an ‘interesting’ program that would not pass these heuristics. A very minimal program can be constructed that outputs interesting video – it can be done in just 32 bytes, even – but this program would not pass the heuristics test. For example, this program creates an animated color pattern on the Atari, but would fail all heuristic tests:

; Program starts at $F000

LDA #$00 ; Start with color 0 / black

STA $2C ; Set background color

INC ; Increment accumulator

JMP $F002 ; Jump to set background color

To find the population of interesting ROMs, you need to run them all. This is the halting problem in action. There is no way to determine if a program will access the video output or will stop dead after a few clock cycles without actually running the entire program.

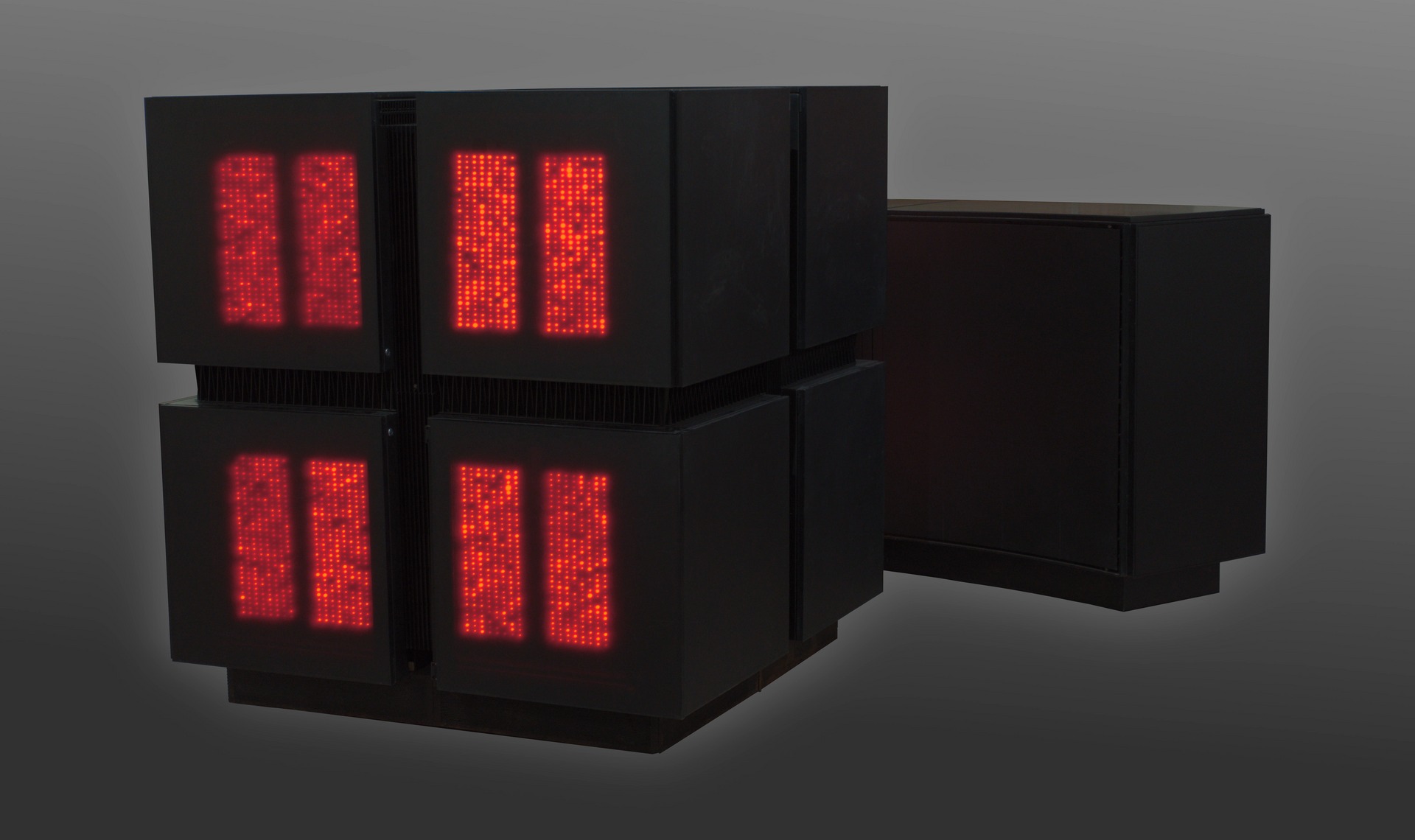

The solution to finding interesting bits of computation in random data would require a massively parallel emulation framework addressing two key limitations of the Atari 2600. The Atari is far too complex even with a parallel emulation framework, and the limited RAM of 128 bytes is much too small for anything interesting to drop out. This led me to look for a better platform for this project.

The answer is CHIP-8. The CHIP-8 provides a stable video interface instead of the Atari’s complex TIA timing requirements and NTSC waveform generation. The CHIP-8 also provides 4kB of directly addressable RAM compared to the Atari’s disjointed memory model of 4kB of ROM and 128 bytes of RAM. Most important for this project, the CHIP-8 is ideal for GPU parallelization. The architecture makes it straightforward to instrument the internal state of the system during emulation.

The goal of this project is to run billions of ROMs in parallel, just to see if something interesting happens. Because of my success with the Finite Atari Machine, this is somewhat of a foregone conclusion, even if it might take a while. But the change to the CHIP-8 platform also allows me to ask a deeper question: If I pre-seed memory with structured data, will a random program ever sort it? Could something like quicksort be found in the program space? The answer, unfortunately, is not in two weeks, and not with 50 billion random CHIP-8 programs.

Technical Implementation

Platform Choice

The first goal of this project is to build an emulator or interpreter that can be run at a massively parallel scale. For this, the choice of the CHIP-8 architecture becomes obvious in retrospect. The CHIP-8 has a number of advantages for this project over the Atari 2600. Of those:

- The CHIP-8 has a uniform instruction width. Every instruction is exactly two bytes. The Atari uses variable-length instructions, where each line of assembly can be one, two, or three bytes long. This simplifies decoding, and knowing when and by how much to increase the Program Counter.

- The CHIP-8 is a virtual machine. This is getting into the weeds a bit, but the Atari is hell for parallelization. Yes, it’s been done with CuLE, but the Atari has instructions that run in two clock cycles, or four, or seven cycles, or something else. This is hell for running multiple instances on a GPU. The CHIP-8, on the other hand, can just… run. One instruction per tick. It’s easy.

- The Atari races the beam. It is a device that generates NTSC (or PAL, or SEACAM) video. Even a ‘headless’ emulator would need to know where the back porch is, where the VBLANK is, count sixty eight clock cycles for each scanline, then another eight for the HBLANK. It’s not a nightmare to emulate, but man, I really don’t want to do this. The CHIP-8, on the other hand, is just a 64x32 pixel framebuffer that is much simpler to write to and decode.

So I had to write a CHIP-8 emulator following Cowgod’s Technical Reference. I want this to be portable so anyone can run it, and a ‘ground truth’ as a reference standard. For this, I’m using Python with tkinter. Think of this version as the ‘development’ branch. It’s a single instance, it will never run on the GPU, but it will be helpful to debug generated ROMs.

This single-instance emulator is insufficient for running in a massive parallel emulation engine. I’ll need another version that runs on a GPU. That’s CuPy. Unlike the single-instance Python version, this version will not have a GUI, although it will keep that framebuffer in memory. There’s no interactive debugging, and everything will be vectorized; I will be able to record everything that happens across ten thousand instances of emulators running in parallel.

Python Implementation

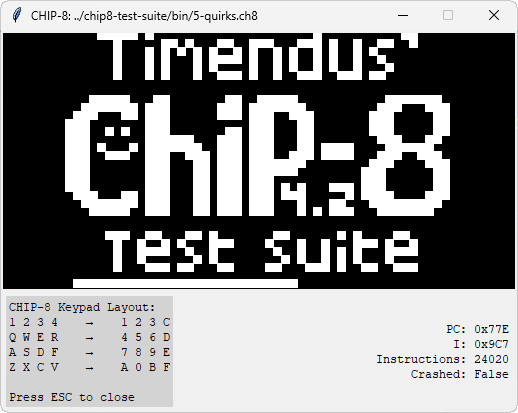

The single-instance development is a thousand or so lines of Python. Other than a 64x32 display, there's not much to it. There are counters in the window showing the Program Counter and Index register -- not that useful but fun to look at -- and a few other status labels showing how many instructions have been executed and whether or not the emulator has crashed or not.

Getting this emulator _right_ was paramount. For this, I used a CHIP-8 Test Suite. These are CHIP-8 programs that test the display, opcodes, flags, keypad, and all the quirks of the CHIP-8 platform. There are a few things I didn't implement. The CHIP-8 has a 'beep' instruction. I'm not implementing that because it's annoying and it really doesn't matter for this. I'm not implementing the 'SUPER-CHIP' or 'XO-CHIP' extensions, because a few of these extensions break the uniform instruction width of the CHIP-8 platform. With a little bit of work, my single-instance emulator passed all of these tests.

The current Python implementation is available on Github

GPU / Parallel Implementation

With the Python implementation complete, I could begin work on the parallel version for CuPy. This is where things sort of fall apart, at least technologically. Implementing parallel emulators requires rethinking the entire architecture around GPU constraints and the realities of warp divergence.

Warp divergence is when threads of a GPU's execution group need to follow different code paths. For example, when one emulator has a conditional branch, while another in the same group has to go another way. This is murder for testing thousands of emulators, all running different _random_ code.

The solution to this is to embrace the divergence rather than fight it. The parallel emulation framework uses masked vectorized operations, where every instruction executes across all instances simultaneously, but boolean masks determine which instances are actually affected.

Let’s say I’m running 10,000 instances of a CHIP-8 emulator, all running different programs. At any given cycle, each instance looks at the Program Counter to fetch the next instruction. 300 instances might have 0x8132 at this memory location – a bitwise AND on the V1 and V3 registers, storing the result in V1. 290 instances have the instruction 0x8410 – setting register V4 equal to V1 The GPU executes all unique instructions on all 10,000 instances, but only changes the state of the 300 instances with the AND instruction, and only increments the Program Counter of the 290 instances with the SET instruction. After all instructions are complete, each instance advances the Program Counter, and the cycle repeats.

Here we’re getting into the brilliance of using the CHIP-8 architecture. There are only 35 instructions, much less than the 150+ instructions of the Atari 2600. This means less time spent on each cycle, and better overall performance of the parallel emulator system.

The core of the parallel implementation is available on Github

Results and Discoveries

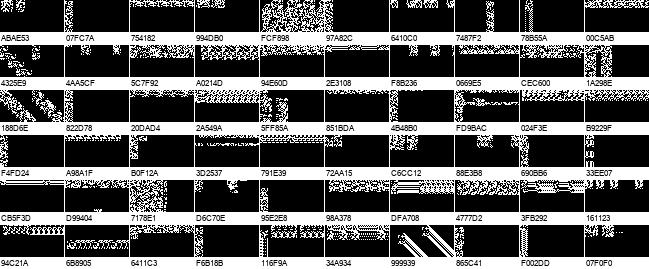

Experiment 1: Finding Random Games

This blog post is already too long and it’s not even halfway done, so I’d like to share some discoveries I’ve made. I started this project by generating random CHIP-8 programs and viewing the output of whatever didn’t crash. Here’s some screencaps of the ouput after a million instructions:

And emulators of some interesting programs:

Program a9c127

Program 7d301

Program e20edb

Program 368cbd

These are the best of the best of about 100 Terabytes of random data.

Program a9c127 was the first interesting program I found because it kinda, sorta looked like a cellular automata. It’s not, because of the biggest weakness of the CHIP-8 platform for this sort of research. Sprite draws in the CHIP-8 are XOR-ed with each other; if an existing pixel is 1, and another pixel is written to the same screen location, the result is a blank pixel. This is a double-edged sword because it does produce the interesting patterns found in other, later programs but it’s not quite as cool as it could be. I could add a NAND or NOR instruction, though. Future research possibilities.

Program e20edb shows the XOR more clearly – it’s a diagonally looping sprite drawing routine with an offset. This is simply writing the same sprite over and over to slightly offset positions. The XOR pattern means these diagonal stripes change over time, eventually disappearing, at which point the cycle repeats.

Programs 368cbd and 7d301 look extremely similar, but they’re distinct ROMs from distinct runs (distinctness proven by the shortened SHA-1 name). They are both simply writing random data as sprite data, XOR-ing the result on the screen. While these programs might not be much to look at, they’re at least as complex as what I found with the Finite Atari Machine.

Experiment 2: Searching for Sorting Algorithms

The entire point of this isn’t to generate cool, broken QR codes on the display of a CHIP-8 emulator. I’ve already proven that’s possible with the Finite Atari Machine. The purpose of this experiment is to find something interesting. Specifically, I want to find something computationally interesting. This means algorithms, for sorting or graph traversal. It could mean cellular automata. A lot of stuff can just fall out of random data if you run it through a computer.

In short, I’m looking for a sorting algorithm in random data.

On Not Discovering A Sorting Algorithm: Method

Stage 1: Things that look like sorting algorithms

The implementation of this is simple. I want to find a sorting algorithm I generate billions of programs filled with random data, and store [8 3 6 1 7 2 5 4] in eight of the sixteen registers of the CHIP-8, in V0 through V7. Then, I fill up the rest of the program space with random bytes, emulate them, and monitor the values in the registers. Emulate billions of these random programs. Eventually, I’ll get a few programs where registers V0 through V3 are [1 2 3 4] or [8 7 6 5].

More rarely, I’ll get programs where registers V0 through V4 are [1 2 3 4 5] or [8 7 6 5 4]. After running this emulator script for a few days, I may even get registers V0 through V7 containing [1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8] or [8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1]. If that happens, I may have found a sorting algorithm in random data. I would need to disassemble the program and step through the instructions to confirm it, but this is a viable way to find quicksort, or bubble sort, or a sorting algorithm no one has thought of before.

For this experiment, I adapted the existing code into two python files. The sorting_emulator.py file is the emulator, sorting_search.py is the ‘runner’ – a script that manages program generation, emulator execution, search, and background tasks like collecting metadata and saving good programs.

sorting_emulator.py View on Github

The core parallel CHIP-8 emulation engine optimized for sorting algorithm detection. This file implements a massively parallel GPU-based emulator using CuPy that can simultaneously run thousands of CHIP-8 instances. Key features include:

- Vectorized instruction execution: All 35 CHIP-8 opcodes implemented as masked vector operations to handle warp divergence efficiently

- Batch generation: Creates randomized CHIP-8 ROMs with the test pattern

[8 3 6 1 7 2 5 4]pre-loaded into registers V0-V7 - Register monitoring: Real-time tracking of V0-V7 registers across all instances to detect sorted sequences

- Pattern detection: Configurable detection of 3+ consecutive sorted elements (ascending or descending) during emulation

- Memory management: Optimized GPU memory allocation for handling large batches of ROM data

- State instrumentation: Comprehensive logging of register states, instruction counts, and execution statistics

- Crash detection: Identifies and filters out instances that hit invalid opcodes or infinite loops

The emulator processes batches of 20,000-500,000 programs simultaneously. It can check register patterns every instruction cycle but this is very computationally expensive; I’m checking the registers every four instruction cycles. All programs run for 100,000 cycles until they’re terminated and the process repeats for another batch of 20,000 to 500,000 programs.

sorting_search.py View on Github

The orchestration and data management layer that coordinates the entire sorting algorithm discovery pipeline. This script handles:

- Search coordination: Manages the execution of multiple emulator batches with configurable search parameters

- Result classification: Sorts discoveries by sequence length (3-element, 4-element, etc.) and saves promising candidates

- Session management: Tracks progress across multi-hour search sessions with detailed logging and recovery capabilities

- Performance monitoring: Real-time statistics on ROM processing rates, discovery rates, and computational efficiency

- Data persistence: Saves discovered sorting algorithms to disk with metadata for later analysis and validation

The search script is designed for long-running exploration sessions, automatically managing GPU resources and providing detailed progress reporting as it searches through billions of random programs.

Stage 2: Things that actually are sorting algorithms

The first stage is a bulk search; it’s simply looking at registers V0 through V7, and seeing if there the registers have the values [8 3 6 1 7 2 5 4] sorted in any way. For example, V0 = 8, V1 = 7, V2 = 6 would count as a 3-element sort, descending. V4 = 5, V5 = 6, V6 = 7, V7 = 8 would count as a 4-element sort, ascending. The following table shows exactly how rare this is and demonstrates the exponential drop-off one would expect.

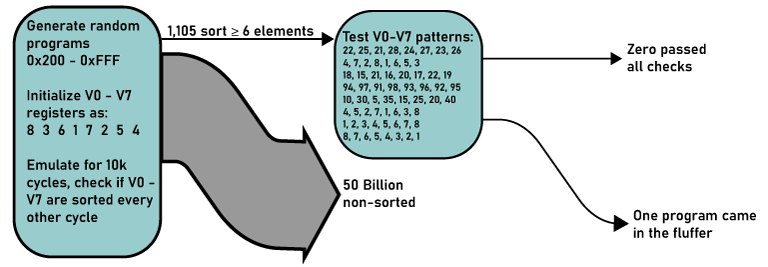

This data set represents over 50 billion ROMs tested across 17 search sessions, consuming 217 hours of GPU time on an RTX 5080. The search yielded 3.47 billion total discoveries, with 174 programs producing complete 8-element sorted sequences. These are the potential sorting algorithms that warrant deeper analysis.

Discovery Rates per Billion ROMs Tested

| Sequence Length | Per Billion ROMs | Rarity Factor |

|---|---|---|

| 3 Elements | 62.8 Million | 1 in 16 |

| 4 Elements | 6.1 Million | 1 in 165 |

| 5 Elements | 31,279 | 1 in 31,947 |

| 6 Elements | 13.8 | 1 in 72.6 Million |

| 7 Elements | 4.7 | 1 in 212.7 Million |

| 8 Elements | 3.5 | 1 in 289.6 Million |

Results From A Week Or Two Of Discovery

After about two weeks of compute time, I had over 1,000 different programs consisting of what could be 6-, 7-, or 8-element sorting algorithms. These again had to be winnowed down to see if there’s anything there.

To find a true sorting algorithm in random data, the fastest approach is to first gather hundreds of programs that could sort, and then test all of those programs with different test data. Whatever falls out after that process is an excellent candidate for decompilation. This requires another test script, rom_generalization_tester.py; this script is available in the Github repo. This script uses the same CUDA emulator as the ‘discovery’ scripts, but it modifies the V0 through V7 registers to test different patterns. The ROM generalizer tests eight patterns:

[22, 25, 21, 28, 24, 27, 23, 26]22-29 range[4, 7, 2, 8, 1, 6, 5, 3]Different permutation of 1-8[18, 15, 21, 16, 20, 17, 22, 19]15-22 range[94, 97, 91, 98, 93, 96, 92, 95]Range in the 90s[10, 30, 5, 35, 15, 25, 20, 40]Mixed spacing[4, 5, 2, 7, 1, 6, 3, 8]Reverse of the original pattern[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]Already sorted[8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1]Reverse sorted

The idea of this being is if a program passes the first test by virtue of being saved in the initial search, and passes these eight tests for sorting, then it’s probably a sorting algorithm. Or at least it’s worth doing the actual decompilation of the program code and figuring out what’s going on.

The results of this generalization tester were disappointing but not unsurprising. No individual program could find a general sorting algorithm that consistently sorted any subset of the registers in question. While they did work with some patterns, most of these ‘discoveries’ generalize into a few different types of errors. These include identity errors, or programs don’t actually sort, they just leave ‘sorted’ data in the registers. Also, pattern-specific manipulation were found. These errors only work on the original [8,3,6,1,7,2,5,4] test pattern. Finally, coincidental consecutive placement was found in the first pass over the data. These programs overwrite the registers with random consecutive numbers. For example, an output of [225,226,227,228,229,230] is not derived from the [8,3,6,1,7,2,5,4] test pattern.

Future Directions

Other Virtual Machine Targets

As discussed in the Finite Atari Project, there are reasons I went with CHIP-8 over more interesting and social media-friendly architectures. The NES and Game Boy have memory mappers, bank switching, and memory protection. Rehashing the Atari involves complex emulation for video output, and 128 bytes of RAM doesn’t allow for very much algorithmic complexity. The CHIP-8 is nearly ideal for this project with a flat memory model, programs that write to their own code area, and a limited number of instructions.

No, I’m not doing Brainfuck, but not for the reason you might imagine. The Babelscope operates on a fixed window of a ~4kB program. “Random Brainfuck” is completely unbounded. You can write anything a computer can do in Brainfuck, but I have no idea how long the program would be. I’m not searching for CHIP-8 programs larger than 4kB simply because of GPU limitations. Not wanting to search the Brainfuck space is a limit of the GPU; there’s no effective way to search an unbounded Brainfuck space. I’m also not doing Brainfuck for the reasons you do imagine.

x86 and ARM are too complex and have variable instruction lengths. RISC-V is nearly perfect with a fixed instruction width and simple addressing. In fact, this project could have been written for RISC-V and would have been much more ‘legitimate’ in the eyes of the the audience that’s reading this. If anyone is going to replicate this project, I would suggest RISC-V, with the caveat that it wouldn’t necessarily have a display output. I needed that, so I went with CHIP-8.

Conclusion

I am immensely pissed off at this project, but not because I didn't find anything. Given enough time -- on the scale of entire lifetimes -- something would eventually fall out of the random data stuffed into a computer. This is a compute-bound problem, solved by writing a little bit of CUDA, and it would take months to find a single algorithm that sorts a handful of registers or finds a Newton-like square root algorithm There are better ways to do this; it's a highly parallelizable problem and there are already data centers running hundreds of thousands of GPUs at full tilt.

Just imagine: instead of training a new LLM model, we could have novel sorting algorithms being spat out of a machine every few minutes. With enough compute, you could brute-force new graph traversal strategies. New compression techniques. Whole classes of useful code might just fall out of noise, if we had enough eyes on it.

Instead, we’re mining the computational space of random programs… to make a chatbot slightly better at writing CSS. And slightly worse at knowing when to stop using em dashes.

That’s not to say this is a good method of algorithm discovery. It’s actually terrible. To find A*, you’d have to boil a lake. No, really, I’ve done the math and it would actually boil some small alpine lakes. Maybe this will be worth a revisit when the GPUs go dark in the next AI winter. I’ll reassess next year.

Finally…

In any event, this entire project is entirely stupid, and about two decades before its time.

Consider what this project would have looked like twenty years ago, in 2005. Back then there was no CUDA and the closest thing to parallel computing anyone could pull off was a Beowulf cluster for the Slashdot street cred. Sinking $100,000 into this project in 2005 would get maybe 100 single-core processors running at around 2 GHz. Instead of testing 250,000 programs simultaneously, I would be lucky to test a hundred at a time.

Now consider what the landscape will look like in twenty years. I’m using an RTX 5080 in the year 2025. Moore’s law broke a while back, but there’s still a trajectory; GPU performance has been growing 25% per year for a while. Compound that over a few decades, and what took me a week in 2025 could be done in ten minutes in 2045. Instead of testing 250,000 programs simultaneously, I could be testing 250 million in parallel. Instead of tying up a GPU for a month, this search could be done over a lunch break.

We wouldn’t even be limited to little ‘toy’ computers like the CHIP-8. With that much compute, we could test real architectures like ARM, RISC-V, or even the last iteration of x86, from before Intel’s bankruptcy in 2031.

Right now, this is the stupidest waste of compute power ever envisioned. But if we don’t blow ourselves up, Taiwan isn’t invaded, and we continue cramming more transistors into GPUs, this could be an interesting tool in a few decades.