Classic Mac OS Development

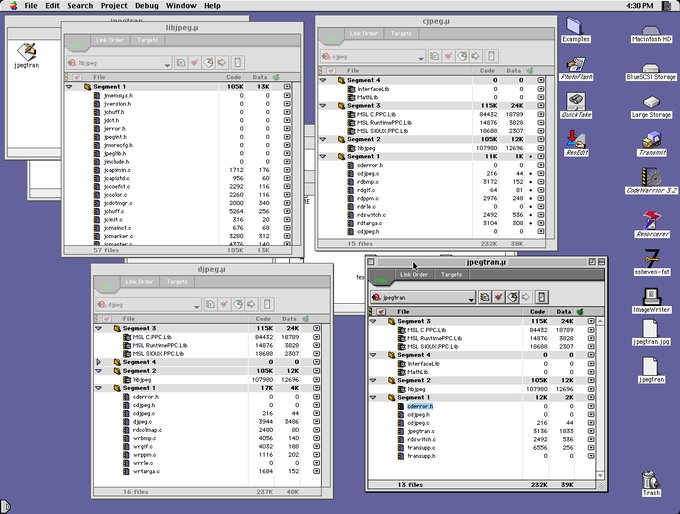

For reasons ranging from my Instagram clone for vintage digital cameras, and my Apple Quicktake photography, I’m in need of a few tools for the classic Mac OS. This includes a small app to drop pictures from a Quicktake to quickly save as JPEGs. I would also like to build a ‘desktop client’ for my Instagram clone. Either way, in 2023 I dove into developing for Classic Mac OS. One thing that caused a lot of headaches starting out was the lack of documentation available on the Internet – the Classic Mac OS was discontinued in 2001, and two decades of bitrot has taken a toll on any documentation relating to development on this platform. My hope is that this page will be a condenced manual on how to get started developing for this platform.

An introduction to Classic Mac OS, and what to target.

The Macintosh was released in 1984, and that computer – the Macintosh 128k – is effectively useless. It cannot run a useful version of of the System Software. Macintosh collectors and the general retrocomputing community eschew the 128k Mac except as an item on a bookshelf. It’s a wonderful collectors piece, but ultimately an item of art, not technology.

The retromac community, at least in the context of the Classic OS, is focused three major segments. The first is 68k machines. These include the aformentioned Mac 128k, but also the considerably more useful Mac Plus, SE, SE/30, as well as LCs and Quadras. The most common operating system for these computers is either System 7.1 or 7.5.3, depending on how much RAM the computer has.

The second segment of retromac usage is beige PowerPCs. Like Apple’s switch from Intel to ARM, or the switch from PowerPC to Intel, this stage of Macintosh development brought an entirely new archetecture. For the developer, this change resulted in new libraries and an explosion of options and preferences in IDEs. Importantly, the switch to PowerPC necessitated the inclusion of 68k emulation in all PowerPC systems. This means most applications written for 68k can run on PowerPC hardware. Most retromac enthusiasts in this camp run at least System 7.5.3, with most opting for 8.6 or Mac OS 9.

After the release of PowerPC, developers sought to release ‘Fat’ applications – programs that ran natively with either 68k or PowerPC chips. This was a great idea at the time, because the transition to PowerPC was, at first, only an incremental improvement. Some 68k programs ran slower on PowerPC hardware. However, in the decade or so between the release of the first and last PowerPC, an increase in clock speeds, bus speeds, and a vast decrease in memory prices meant even the least expensive iMac was more than capable of running any 68k application faster than it ever could on native hardware.

The third segment of the retromac community is the post-iMac era. This includes the original iMac up to G5 Mac Pros. These machines do not have a serial port (important for my Quicktake experiments). Almost exclusively, these machines are running OS 9 if not OS X under compatibility mode. These machines can also run 68k applications easily.

The specs for these machines vary greatly. The lowest-end, either a Mac Plus or Mac SE, come with one to four megabytes of memory. The screen resolution is 512×342 pixels. When it comes to networking, these machines use the MacTCP stak, an extremley slow network stack capable of about 40kB/sec. Newer macs have gobs of memory, up to a gigabyte in some cases, screen resolutions of up to 1600x1200 pixels, much faster networking stacks, and support for “multimedia” applications through Quicktime.

We’re casting a wide net when programming classic Mac applications. Ideally, a program should support an SE/30 at the minimum, and a fancy G4 cube running in classic compatability mode at the most. That’s about a decade of computers sold by Apple, in an era where performance and capabilities of those computers expanded greatly. This is a challenge.