Recreating the Connection Machine: 4,096 RISC-V Cores in a Hypercube

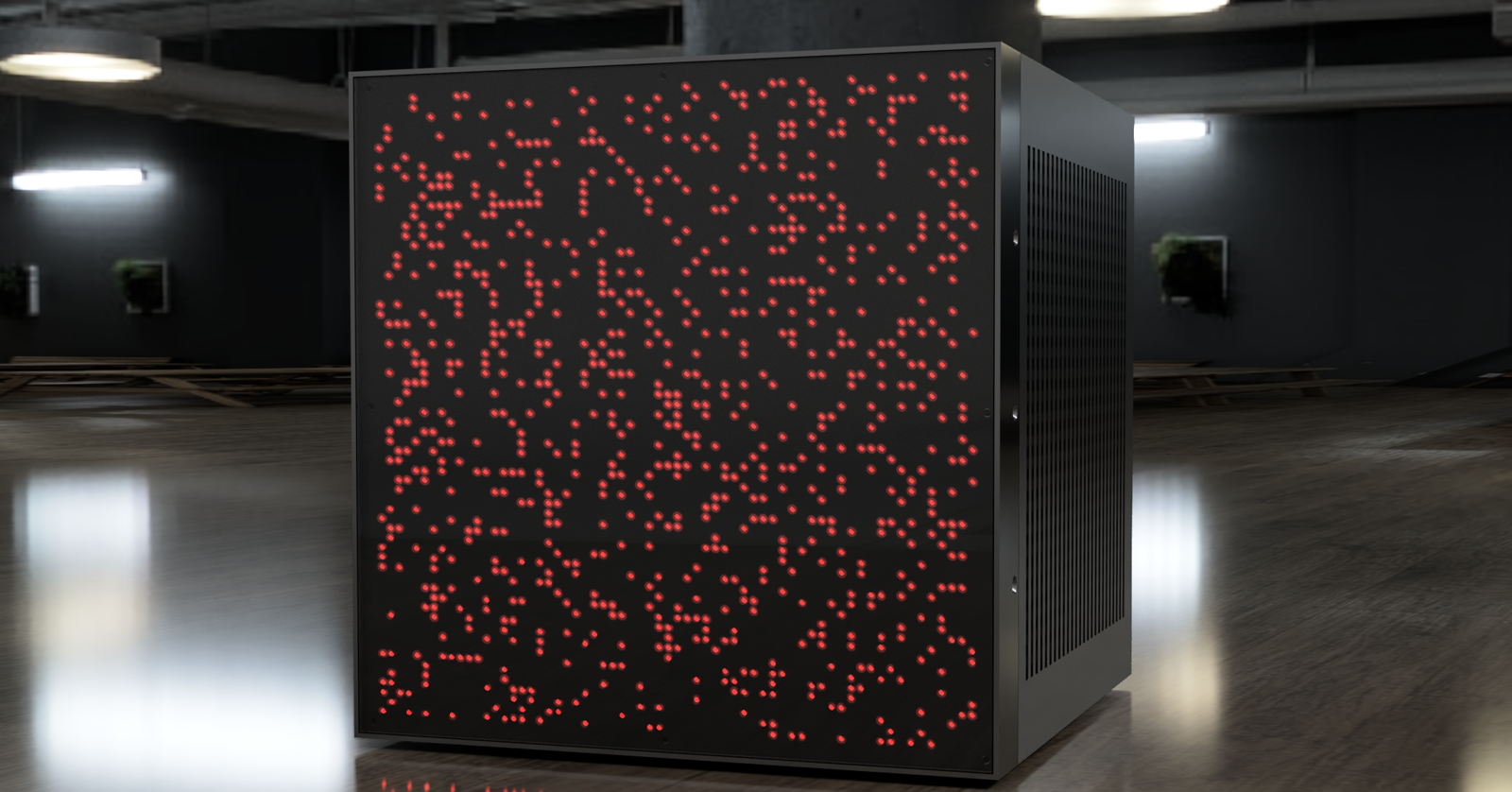

I made a supercomputer out of a bunch of smartphone connectors, chips from RGB mechanical keyboards, and four thousand RISC-V microcontrollers. On paper, it has a combined clock rate over one Terahertz. The memory bandwidth is several Gigabits per second. These are real numbers, because I remember old issues of PC Gamer and their ilk doing the same thing. It’s faster than your laptop on some matrix operations. But that’s on paper. In reality, it can’t run Doom. But it will do beautiful and cursed parallel math behind a smoked acrylic panel studded with blinkenlights.

Introduction

In 1985, Thinking Machines built the Connection Machine CM-1. This was a parallel computer with 65,536 individual processors arranged at the vertexes of a 16-dimension hypercube. This means each processor in the machine is connected to 16 adjacent processors.

The Connection Machine was the fastest computer on the planet in the late 1980s (The Top500 list of supercomputers only goes back to 1993), and was purchased by various three-letter agencies, NASA, and a few well-funded universities.

Like most tech companies, Thinking Machines was a defense contractor pretending to be a cool and exciting business. When the Cold War ended, DARPA cut their funding and the company officially died in 1994. By this time, Moore’s Law had kicked in and workstations from Sun (and others) made the idea of a five million dollar machine that only spoke Lisp untenable for most companies.

Blame Gorbachev or the second AI winter, by the mid 1990s Thinking Machines was dead. By the turn of the millenium, all of the Connection Machines were out of service. There’s one in the New York MoMA, but it’s not on display. Same with the Smithsonian. There’s one at the Computer History Museum, but the lights don’t work. The Living Computers museum had one, but it has since disappeared.

The machines that remain don’t work, and there’s zero code available for these machines. So I built one.

This project is a modern recreation or reinterpretation of the lowest-spec Connection Machine built. It contains 4,096 individual RISC-V processors, each connected to 12 neighbors in a 12-dimensional hypercube.

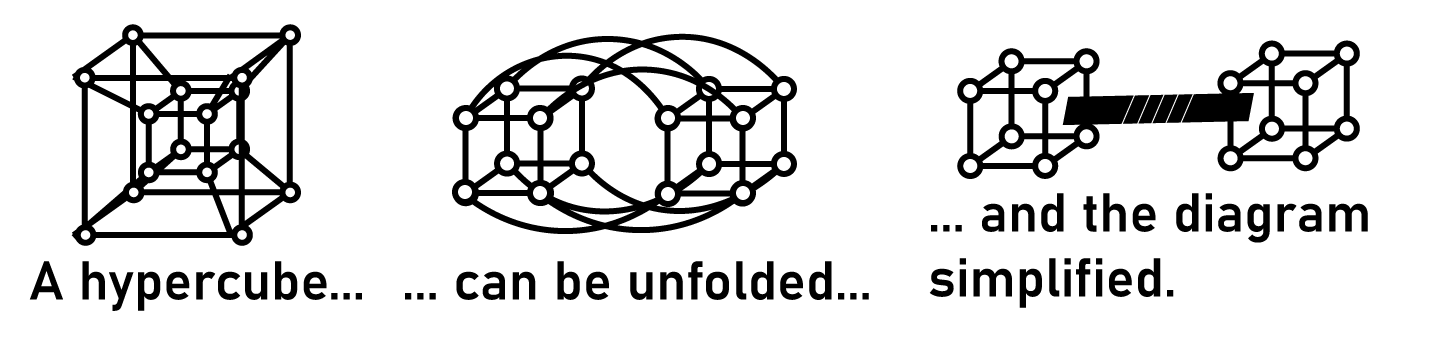

The Connection Machine was an early experiment in massive parallelism. Today, a ‘massively parallel computer’ means wiring up a bunch of machines running Linux to an Ethernet switch. The Connection Machine is different. In a machine with 65,536 processor, every processor is connected to 16 other processors. In my machine, there are 4,096 processors, with each one connected to 12 others. For n total processors, each node connects to exactly $\log_2(n)$ neighbors. This topology makes the machine extremely interesting with regard to what it can calculate efficiently, namely matrix operations, which is the basis of the third AI boom.

The individual processors in the original CM-1 couldn’t do much. These processors could only operate on a single bit at a time. This project leverages 40 years of Moore’s law to put small, cheap microcontrollers into a parallel array.

If I wanted this thing on the front page of Hacker News for twelve hours I’d call this, ‘a distraction-free computational platform’ and stuff a box full of Raspberry Pis. But I’m not doing that. This is a reproduction, or a recreation, or an ‘inspired by’ build of the 1986-era Connection Machine, plus 40 years of Moore’s law and very poor impulse control.

In 1986, this was the cutting edge of parallel computing and AI. In 2006, NASA would have used this machine for hypersonic computational fluid dynamics for the rocket that would put humans on the moon by the year 2020. In 2026, it’s a weird art project with a lot of LEDs.

The LED Panel

Listen, we all know why you’re reading this, so I’m going to start off with the LED array before digging into massively parallel hypercube supercomputer. A million people will read this page, and all but a thousand will think this is the coolest part. Such is life.

The Connection Machine was defined by a giant array of LEDs. It’s the reason there’s one of these in the MoMA, so I need 4,096 LEDs showing the state of every parallel processor in this machine. Also, blinky equals cool equals eyeballs, so there’s that.

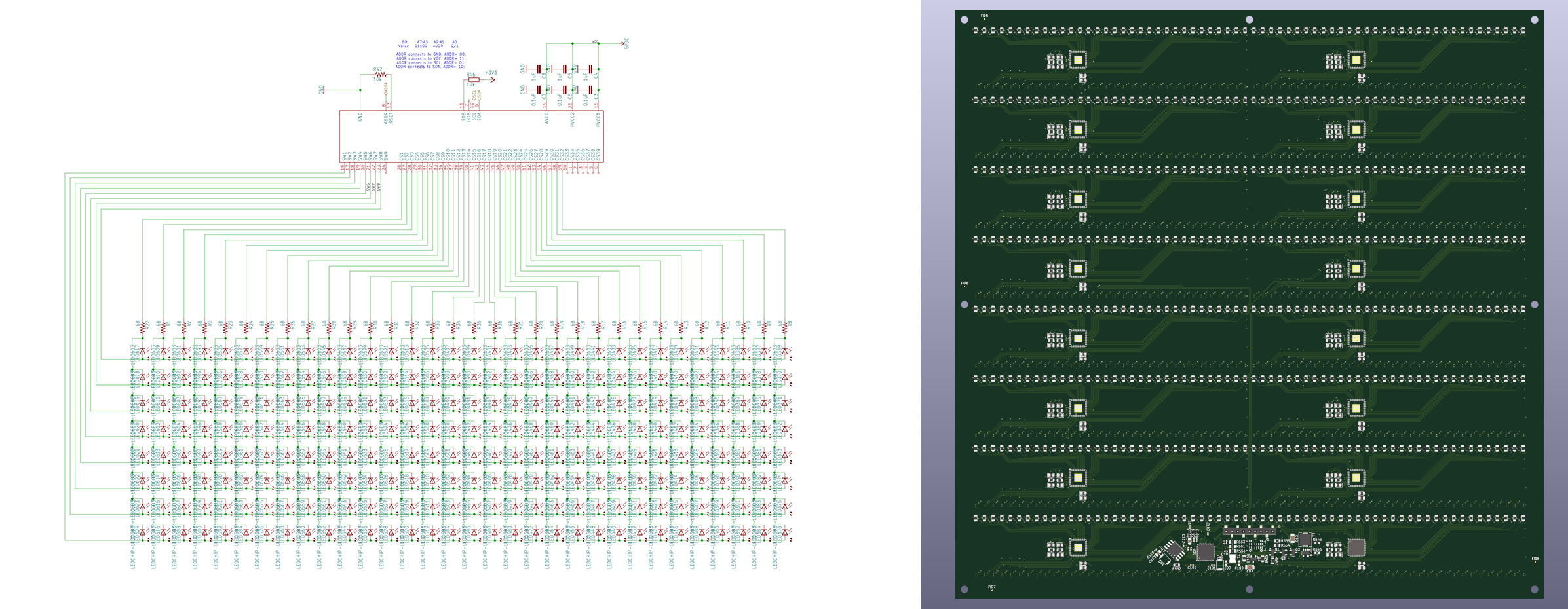

The LED board is built around the IS31FL3741, an I2C LED matrix driver ostensibly designed for mechanical keyboard backlighting. I’ve built several project around this chip, and have a few of these now-discontinued chips in storage.

Each IS31FL3741 is controlling a 8x32 matrix of LEDs over I2C. These chips have an I2C address pin with four possible values, allowing me to control a 32x32 array over a single I2C bus. Four of these arrays are combined onto a single PCB, along with an RP2040 (a Raspberry Pi Pico) microcontroller to run the whole thing.

LED Hardware

- The RP2040 drives 16 IS31FL3741 chips over four I²C buses.

- It uses PIO-based I²C with DMA transfers to blast out pixel data fast enough for real-time updates.

- The data input is flexible:

- Stream pixel data over serial from another microcontroller

- Or run over USB, treating the RP2040 as a standalone LED controller

Why did I build my own 64x64 LED array, instead of using an off-the-shelf HUB75 LED panel? It would have certainly been cheaper – a 64x64 LED panel can be bought on Amazon for under $50. Basically, I wanted some practice with high-density design before diving into routing a 12-dimension hypercube. It’s also a quick win, giving me something to look at while routing hundreds of thousands of connections.

Mechanically, the LED panel is a piece of FR4 screwed to the chassis of the machine. The front acrylic is Chemcast Black LED plastic sheet from TAP Plastics, secured to the PCB with magnets epoxied to the back side of the acrylic into milled slots. These magnets attach to magnets epoxied to the frame, behind the PCB. This Chemcast plastic is apparently the same material as the Adafruit Black LED Diffusion Acrylic, and it works exactly as advertised. Somehow, the Chemcast plastic turns the point source of an LED into a square at the surface of the machine. You can’t photograph it, but in person it’s spectacular.

LED Software

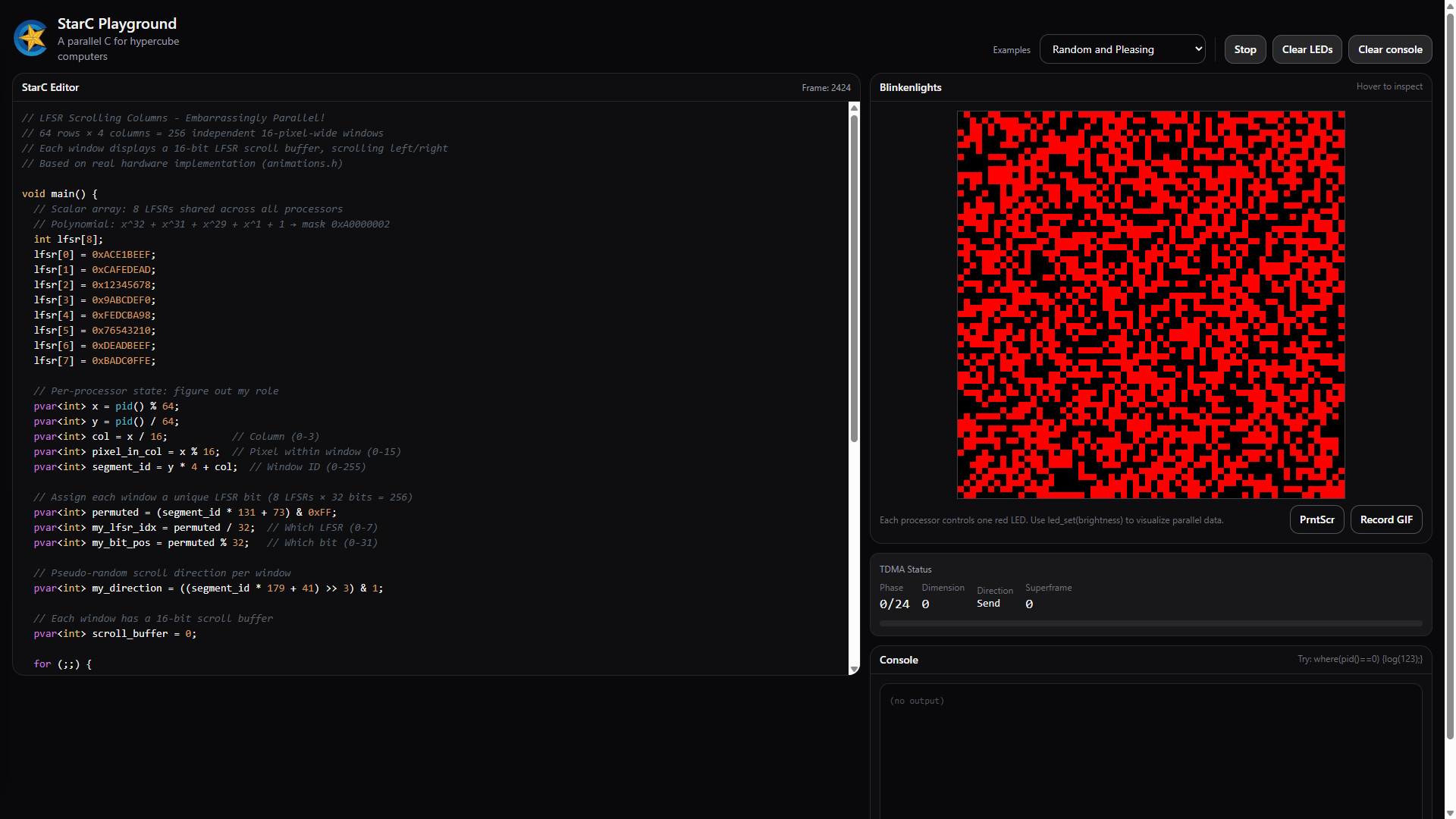

There are a few pre-programmed modes for this panel. Of course I had to implement Conway’s Game of Life, but the real showstopper is the “Random and Pleasing” mode. This is the mode shown in Jurassic Park, and it’s what MoMA turns on when they light up their machine.

There are several sources describing this mode, but only sparse details on how it’s implemented. Trammell Hudson dug into this and the basic idea is, “each processor steps through memory, and sends the bitwise OR of the memory for each processor to one LED.” That’s the CM-1. For the CM-2, it’s basically stepping through random memory. However, every single ‘reverse engineering by looking at it’ attempt implements an LFSR to generate the pixels on the grid. This is (pseudo)random, and also has the effect that the LEDs scroll left or right instead of just blinking like random static.

I went for a 4094-bit LFSR (256 taps), and divided the display up into four columns of 1x16 ‘cells’. These cells are randomly assigned to shift left or shift right, and 256 unique taps are assigned to a particular 1x16 cell. This is so much better than what you see whenever MoMA pulls their machine out of storage. It’s a digital shimmer. It’s an oil stain in a puddle in a parking lot. It’s beautiful.

My Machine, Overview

This post has already gone on far too long without a proper explanation of what I’m building.

Very very simply, this is a very, very large cluster of very, very small computers. The Connection Machine was designed as a massively parallel computer first. The entire idea was to stuff as many computers into a box, and connect those computers together. The problem then becomes how to connect these computers. If you read Danny Hillis’ dissertation, there were several network topologies to choose from.

The nodes – the tiny processors that make up the cluster – could have been arranged as a (binary) tree, but this would have the downside of a communications bottleneck at the root of the tree. They could have been connected with a crossbar – effectively connecting every node to every other node. A full crossbar requires N², where N is the number of nodes. While this might work with ~256 nodes, it does not scale to thousands of nodes in silicon or hardware. Hashnets were also considered, where everything was connected randomly. This is too much of a mind trip to do anything useful.

The Connection Machine settled on a hypercube layout, where in a network of 8 nodes (a 3D cube), each node would be connected to 3 adjacent nodes. In a network of 16 nodes (4D, a tesseract), each node would have 4 connections. A network of 4,096 nodes would have 12 connections per node, and a network of 65,536 nodes would have 16 connections per node.

The advantages to this layout are that routing algorithms for passing messages between nodes are simple, and there are redundant paths between nodes. If you want to build a hypercluster of tiny computers, you build it as a hypercube.

Hardware Architecture

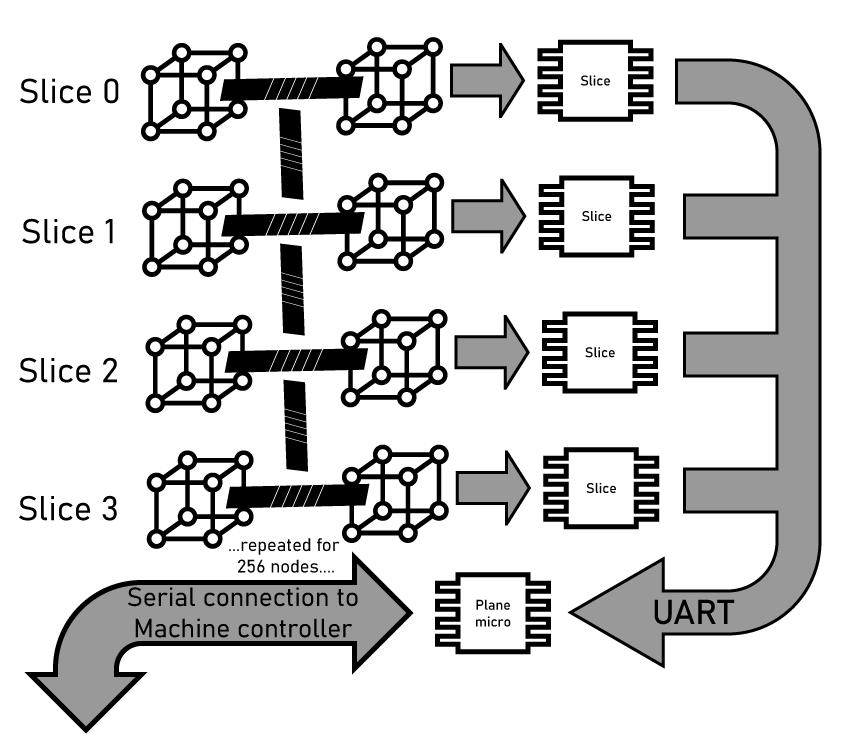

This machine is split up into segments of various sizes. Each segment is 16× bigger than the previous. These are:

- The Node This is just a small RISC-V microcontroller, controlled by another microcontroller.

- The Slice This is 16 individual nodes, connected as a 4-dimension hypercube. In the Slice, a seventeenth microcontroller handles the initialization and control of each individual node. This means providing the means to program and read out memory from each node individually.

- The Plane 16 Slices. The Plane is 256 microcontrollers are connected as an 8-dimension hypercube. There are sixteen ‘slice controller’ microcontrollers, plus one additional ‘plane controller’. This means each plane consists of 273 individual chips.

- The Machine Sixteen Planes make a Machine. The architecture follows the growth we’ve seen up to now, with 4096 ‘node’ microcontrollers connected as a 12-dimensional hypercube. There are 4368 chips in The Machine, all controlled with a rather large SoC.

Like the original Connection Machine, there are two ‘modes’ of connection between the nodes in the array. The first is the hypercube connection, where each node connects to other nodes. The second is a tree. Each node in the machine is connected to the ‘Slice controller’ via UART. This Slice controller handles reset, boot, programming, and loading data into each node. Above the Slice is the Plane and a single ‘plane controller’ for each group of 256 nodes. And above that is the master controller.

This “hypercube and tree” is seen in other massively parallel machines of the 1980s. The Cosmic Cube at Caltech split the connections with individual links between nodes and a tree structure to a ‘master’ unit. The Intel iPSC used a similar layout, but routing subsets of the hypercube through MUXes and Ethernet, with a separate connection to a ‘cube manager’. Likewise, the Connection Machine could only function when connected to a VAX that handled the program loading and getting data out of the hypercube.

Which Microcontroller To Use

The original inspiration for this build is bitluni’s CH32V003-based Cheap RISC-V Supercluster for $2, and it would make sense to focus on something in the CH32V family. They’re cheap, they’re available on LCSC, and they’re reasonably well supported. The CH32V003 is weird though; it only has one UART interface, and the ‘hypercube and tree’ architecture really needs at least two UARTs. Programming the ‘003 chip is just slightly more difficult than I would want.

An alternative to the CH32V003 is the CH32V203. This is a faster, more capable chip based on a RISC-V4B core. It has one-cycle hardware multiply. It’s easier to program. The CH32V003 is thirteen cents in quantity, the CH32V203 is thirty-seven cents in quantity. If I’m going this far, I’ll spend the extra thousand dollars to get a machine that’s a hundred times better.

However, the CH32V203 is not the ideal choice for this machine. A key consideration to chip selection is that the second (hypercube) UART must be capable of being assigned to any pin. The CH32V203 does not have this capability; the USART1_TX can only be mapped to pins PA9 or PB6. The reason we need UART pins fully remapable are covered below, but it is a requirement for the full machine.

Most other microcontrollers have this limitation of peripherals that can only be assigned to specific pins. The PY32 series of ARM Cortex chips support up to five UARTs, but the TX and RX of these UARTs are limited to specific pairs of pins. This is a big limitation for my machine, and I wonder why fully remappable peripherals aren’t as common as I would like. Is there a patent or some shit?

There are several microcontrollers that do have fully remappable peripherals, where a UART can be attached to any pin. The NXP LPC800 series has fully remappable pins, but it’s a slightly expensive part and limited to a CPU frequency of 15MHz. The LPC800 is also an Arm Cortex-M0+ microcontroller, not a RISC-V part. This different architecture is a critical shortcoming if I want to target the Twitter, Reddit, and Hacker News crowds for this project. I gotta get eyeballs on this, after all.

The Cypress / Infineon PSOC has remappable peripherals, but these parts are even more expensive than the LPC800. The Microchip PIC32MM has a crossbar called a ‘peripheral pin select’, but it’s 2026 and I’m not using a PIC. The Raspberry Pi Pico RP2350 has PIOs, or small state machines that can assign functions to any pin. The RP2350 also has (optional) RISC-V cores, perfect for the people who appreciate tech YouTubers telling them what to think. The Pico is an expensive part, though. On paper, the RP2354A – the part with an integrated 2MB NOR Flash – could work. But having exactly as many PIOs as the number of hypercube dimensions is clunky. The Pico is right on the cusp of being workable for this machine, but not enough so that it would be easy to make it work.

There is a better option: The AG32 SoC family from AGM Micro. This family combines a RISC-V microcontroller core with a small (2000 LUT) FPGA fabric. The chip is essentially a RISC-V core, with all pins broken out to an FPGA fabric. With this, I can remap UARTS dynamically and talk to the hypercube nodes without bogging down the RISC-V core. The smallest AG32 is available for eighty cents in quantity from LCSC in a QFN32 package. This is almost the ideal chip.

The AG32 has one significant shortcoming: there is zero documentation in English. The plan is to build up as much of the machine as I can using the CH32V203. In parallel, I’ll work on getting a build system working for the AG32-series microcontrollers. Eventually, hopefully, the full machine will use thousands of these really cool RISC-V + FPGA microcontrollers.

1 Node

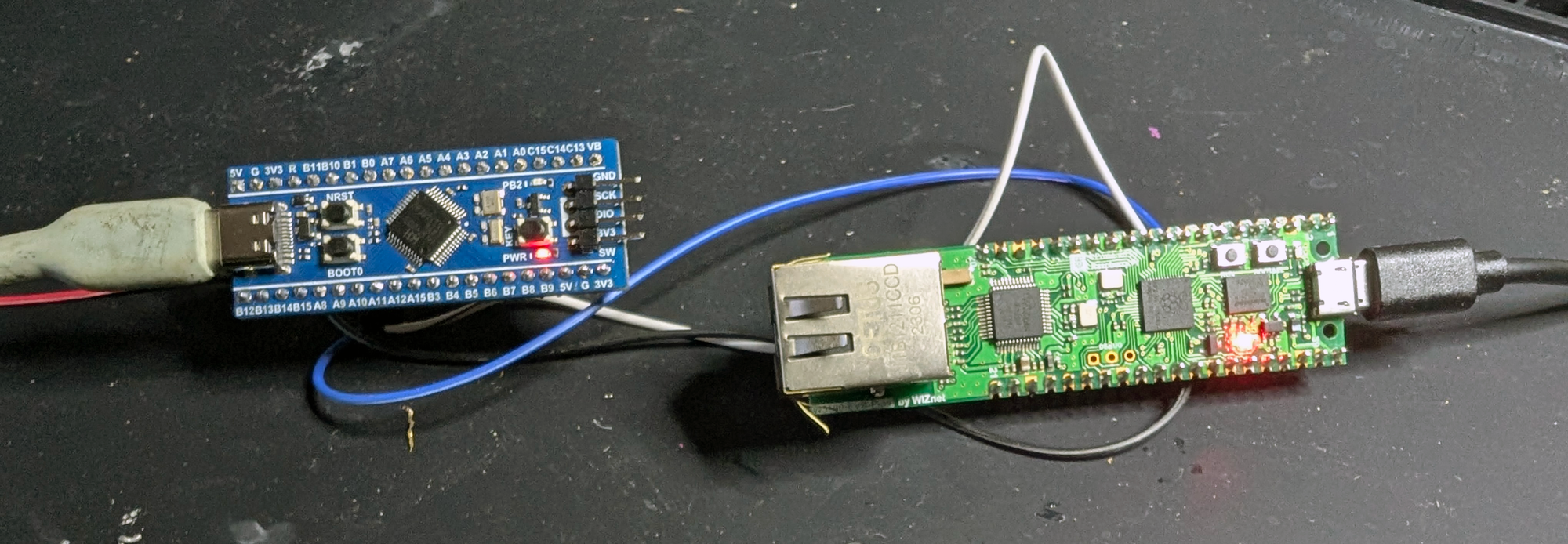

The goal of the 1-node prototype is to program a cheap RISC-V microcontroller with another microcontroller. This can be done with a dev/breakout board for any of the cheap RISC-V chips, so I found the WeAct Studio CH32V203C8T6. After receiving the CH32V203 dev board, I wired it up to the closest Raspberry Pi Pico-shaped object within reach:

It’s just serial lines between two chips. The code is where things get fun.

The CH32V203 can be programmed over a UART presented on pins PA9 and PA10. This is easy enough to wire up, the problem comes when trying to talk to the bootloader in the CH32V203.

There’s an WCH RISC-V Microcontroller Web Serial ISP that will program these chips for you, provided you have a USB to UART converter and a firmware file for the program you want to run on this chip. For a user, the process is pretty simple, you just hold down the Boot0 pin and click upload. Underneath the hood things fall off the rails. Programming the chip works like this:

- Listen to the chip in bootloader mode - the CH32 will send data over the serial connection, and this requires a “password”, a fixed ASCII string that’s

MCU ISP & WCH.CN. The bootloader rejects everything if you don’t send that exact string. - Read the chip config - the programmer sends a bitmask to read everything, and the CH32 sends back option bytes (can the Flash memory be programmed?), the bootloader version, and an 8-byte unique ID (UID)

- Generate a Key - creates a random seed length of 30 bytes, computes a ‘seed’ with the UID and random seed, computes an 8-byte key using specific indexes from that seed and XORs it with the UID checksum. This is sent to the bootloader, and the bootloader replies with a key checksum byte, that should match what the programmer has. Why the hell it does this I have no idea. You already have physical access to the chip, what’s the threat model here?

- Erases all the flash

- Writes the new program in chunks of 56 bytes, XORed with the key

- Generates a key again

- Verifies the flash with the new key

- Resets the CH32, letting it start up with the firmware you just wrote.

Yes, this was a massive pain to figure out what was actually happening. The good news is I didn’t have to do all the work. The WCH-web-ISP code is right there, so I just told the RP2040 to do whatever the Javascript on that page was doing.

The actual payload can be anything I want. I whipped up a slightly more sophisticated ‘Hello World’ and ‘Blink a LED’ program for the CH32, compiled it, and created a firmware.h file for the Pico uploader. The contents of this .h file is just a hex dump of the .bin file built by the compiler.

The full code listing of the Pico uploader is available here:

#include <Arduino.h>

// ---------- Embedded firmware ----------

#include "firmware.h"

static const uint32_t HOST_BAUD = 115200;

static const uint32_t TARGET_BAUD = 115200;

// Pico GPIOs -> CH32 pins

static const int PIN_BOOT0 = -1; // -> CH32 BOOT0 (active high)

static const int PIN_NRST = -1; // -> CH32 NRST (active low)

static const int PIN_UART_TX = 4; // Pico TX -> CH32 RX (PA10)

static const int PIN_UART_RX = 5; // Pico RX <- CH32 TX (PA9)

static const uint8_t DEV_VARIANT_REQ = 0x31;

static const uint8_t DEV_TYPE_REQ = 0x19;

static uint8_t g_dev_variant = DEV_VARIANT_REQ;

static uint8_t g_dev_type = DEV_TYPE_REQ;

// Packet headers (packet.js)

static const uint8_t HDR_CMD0 = 0x57, HDR_CMD1 = 0xAB;

static const uint8_t HDR_RSP0 = 0x55, HDR_RSP1 = 0xAA;

// Command codes (command.js)

static const uint8_t CMD_IDENTIFY = 0xA1;

static const uint8_t CMD_END = 0xA2;

static const uint8_t CMD_KEY = 0xA3;

static const uint8_t CMD_FLASH_ERASE = 0xA4;

static const uint8_t CMD_FLASH_WRITE = 0xA5;

static const uint8_t CMD_FLASH_VERIFY = 0xA6;

static const uint8_t CMD_CFG_READ = 0xA7;

static const size_t CHUNK_SIZE = 56;

static bool readByteTimeout(Stream &s, uint8_t &out, uint32_t timeoutMs) {

uint32_t t0 = millis();

while (millis() - t0 < timeoutMs) {

int c = s.read();

if (c >= 0) { out = (uint8_t)c; return true; }

delay(1);

}

return false;

}

static bool readExactTimeout(Stream &s, uint8_t *dst, size_t n, uint32_t timeoutMs) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if (!readByteTimeout(s, dst[i], timeoutMs)) return false;

}

return true;

}

static uint8_t sum8(const uint8_t *p, size_t n) {

uint32_t s = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) s += p[i];

return (uint8_t)(s & 0xFF);

}

static void hexDump(const uint8_t *p, size_t n) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if (p[i] < 16) Serial.print('0');

Serial.print(p[i], HEX);

}

}

static void enterBootloader() {

Serial.println("MANUAL STEP: Put CH32 into bootloader now (BOOT0=1, reset/power-cycle), then send command again.");

}

static void runUserApp() {

Serial.println("MANUAL STEP: Set BOOT0=0 and reset/power-cycle CH32 to run user app.");

}

// ---------- Packet TX/RX ----------

struct Resp {

uint8_t code = 0;

uint8_t b1 = 0;

uint16_t len = 0;

uint8_t data[64];

};

static bool sendCommand(uint8_t cmd, const uint8_t *data, uint16_t len) {

const uint16_t payloadLen = (uint16_t)(3 + len);

uint8_t payload[3 + 256];

if (len > 256) return false;

payload[0] = cmd;

payload[1] = (uint8_t)(len & 0xFF);

payload[2] = (uint8_t)(len >> 8);

if (len) memcpy(&payload[3], data, len);

uint8_t chk = sum8(payload, payloadLen);

Serial1.write(HDR_CMD0);

Serial1.write(HDR_CMD1);

Serial1.write(payload, payloadLen);

Serial1.write(chk);

Serial1.flush();

return true;

}

static bool recvResponse(Resp &r, uint32_t timeoutMs = 3000) {

uint8_t b = 0;

// Hunt header 55 AA

while (true) {

if (!readByteTimeout(Serial1, b, timeoutMs)) return false;

if (b != HDR_RSP0) continue;

if (!readByteTimeout(Serial1, b, timeoutMs)) return false;

if (b == HDR_RSP1) break;

}

uint8_t p0, p1, lenLo, lenHi;

if (!readByteTimeout(Serial1, p0, timeoutMs)) return false;

if (!readByteTimeout(Serial1, p1, timeoutMs)) return false;

if (!readByteTimeout(Serial1, lenLo, timeoutMs)) return false;

if (!readByteTimeout(Serial1, lenHi, timeoutMs)) return false;

uint16_t len = (uint16_t)(lenLo | (lenHi << 8));

if (len > sizeof(r.data)) return false;

if (!readExactTimeout(Serial1, r.data, len, timeoutMs)) return false;

uint8_t chk = 0;

if (!readByteTimeout(Serial1, chk, timeoutMs)) return false;

// checksum over payload bytes only

uint8_t hdr[4] = { p0, p1, lenLo, lenHi };

uint32_t s = sum8(hdr, 4);

for (uint16_t i = 0; i < len; i++) s += r.data[i];

if (((uint8_t)s) != chk) return false;

r.code = p0;

r.b1 = p1;

r.len = len;

return true;

}

static bool request(uint8_t cmd, const uint8_t *data, uint16_t len, Resp &r, uint32_t timeoutMs = 3000) {

if (!sendCommand(cmd, data, len)) return false;

if (!recvResponse(r, timeoutMs)) return false;

return (r.code == cmd);

}

// ---------- Device state ----------

static uint8_t optBytes[8];

static uint8_t chipUID[8];

static uint8_t keyBytes[8];

// ---------- Commands ----------

static bool cmdIdentify() {

const char passwd[] = "MCU ISP & WCH.CN"; // 16 bytes

uint8_t data[2 + 16];

data[0] = DEV_VARIANT_REQ;

data[1] = DEV_TYPE_REQ;

memcpy(&data[2], passwd, 16);

Resp r;

if (!request(CMD_IDENTIFY, data, sizeof(data), r)) return false;

if (r.len != 2) return false;

if (r.data[0] >= 0xF0) return false; // bad password etc.

// IMPORTANT: save what it *reported*

g_dev_variant = r.data[0];

g_dev_type = r.data[1];

Serial.print("IDENT OK. variant=0x"); Serial.print(g_dev_variant, HEX);

Serial.print(" type=0x"); Serial.println(g_dev_type, HEX);

return true;

}

static bool cmdConfigRead() {

uint8_t data[2] = { 0x1F, 0x00 };

Resp r;

if (!request(CMD_CFG_READ, data, sizeof(data), r)) return false;

if (r.len != 26) return false;

if (r.data[0] == 0x00) return false;

optBytes[0] = r.data[2];

optBytes[1] = r.data[4];

optBytes[2] = r.data[6];

optBytes[3] = r.data[8];

optBytes[4] = r.data[10];

optBytes[5] = r.data[11];

optBytes[6] = r.data[12];

optBytes[7] = r.data[13];

memcpy(chipUID, &r.data[18], 8);

Serial.print("CFG RDPR=0x"); Serial.print(optBytes[0], HEX);

Serial.print(" USER=0x"); Serial.print(optBytes[1], HEX);

Serial.print(" UID="); hexDump(chipUID, 8);

Serial.println();

return true;

}

static uint32_t rngState = 0xA5A5A5A5;

static uint8_t prng8() {

rngState ^= rngState << 13;

rngState ^= rngState >> 17;

rngState ^= rngState << 5;

return (uint8_t)(rngState & 0xFF);

}

static bool cmdKeyGenerate(uint8_t seedLen = 60) {

if (seedLen < 30) seedLen = 30;

if (seedLen > 60) seedLen = 60;

uint8_t seed[60];

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < seedLen; i++) seed[i] = prng8();

uint8_t uidChk = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) uidChk = (uint8_t)((uidChk + chipUID[i]) & 0xFF);

const uint8_t a = (uint8_t)(seedLen / 5);

const uint8_t b = (uint8_t)(seedLen / 7);

keyBytes[0] = uidChk ^ seed[b * 4];

keyBytes[1] = uidChk ^ seed[a];

keyBytes[2] = uidChk ^ seed[b];

keyBytes[3] = uidChk ^ seed[b * 6];

keyBytes[4] = uidChk ^ seed[b * 3];

keyBytes[5] = uidChk ^ seed[a * 3];

keyBytes[6] = uidChk ^ seed[b * 5];

keyBytes[7] = (uint8_t)((keyBytes[0] + g_dev_variant) & 0xFF);

uint8_t keyChk = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) keyChk = (uint8_t)((keyChk + keyBytes[i]) & 0xFF);

Resp r;

if (!request(CMD_KEY, seed, seedLen, r)) return false;

if (r.len != 2) return false;

if (r.data[0] == 0x00) return false;

if (r.data[0] != keyChk) {

Serial.print("KEYCHK mismatch: host=0x"); Serial.print(keyChk, HEX);

Serial.print(" boot=0x"); Serial.println(r.data[0], HEX);

return false;

}

Serial.print("KEY OK key="); hexDump(keyBytes, 8); Serial.println();

return true;

}

static bool cmdFlashErase(uint32_t sectors1k) {

uint8_t data[4] = {

(uint8_t)(sectors1k & 0xFF),

(uint8_t)((sectors1k >> 8) & 0xFF),

(uint8_t)((sectors1k >> 16) & 0xFF),

(uint8_t)((sectors1k >> 24) & 0xFF),

};

Resp r;

if (!request(CMD_FLASH_ERASE, data, sizeof(data), r, 5000)) return false;

return (r.len == 2 && r.data[0] == 0x00);

}

static void xorEncrypt(uint8_t *dst, const uint8_t *src, size_t n) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) dst[i] = (uint8_t)(src[i] ^ keyBytes[i % 8]);

}

static bool cmdFlashWriteChunk(uint32_t addr, const uint8_t *plain, uint16_t n) {

uint8_t data[5 + CHUNK_SIZE];

data[0] = (uint8_t)(addr & 0xFF);

data[1] = (uint8_t)((addr >> 8) & 0xFF);

data[2] = (uint8_t)((addr >> 16) & 0xFF);

data[3] = (uint8_t)((addr >> 24) & 0xFF);

data[4] = 0x00;

if (n > 0) xorEncrypt(&data[5], plain, n);

Resp r;

if (!request(CMD_FLASH_WRITE, data, (uint16_t)(5 + n), r, 3000)) return false;

return (r.len == 2 && r.data[0] == 0x00);

}

static bool cmdFlashWriteFinalize(uint32_t endAddr) {

return cmdFlashWriteChunk(endAddr, nullptr, 0);

}

static bool cmdFlashVerifyChunk(uint32_t addr, const uint8_t *plain, uint16_t n) {

uint8_t data[5 + CHUNK_SIZE];

data[0] = (uint8_t)(addr & 0xFF);

data[1] = (uint8_t)((addr >> 8) & 0xFF);

data[2] = (uint8_t)((addr >> 16) & 0xFF);

data[3] = (uint8_t)((addr >> 24) & 0xFF);

data[4] = 0x00;

if (n > 0) xorEncrypt(&data[5], plain, n);

Resp r;

if (!request(CMD_FLASH_VERIFY, data, (uint16_t)(5 + n), r, 3000)) return false;

return (r.len == 2 && r.data[0] == 0x00);

}

static bool cmdEnd(bool doReset) {

uint8_t data[1] = { (uint8_t)(doReset ? 0x01 : 0x00) };

Resp r;

if (!request(CMD_END, data, sizeof(data), r, 3000)) return false;

return (r.len == 2 && r.data[0] == 0x00);

}

static bool programEmbedded(bool verify) {

const uint8_t *fw = firmware_bin;

const uint32_t fwLen = (uint32_t)firmware_bin_len;

Serial.print("FW size: "); Serial.println(fwLen);

enterBootloader();

if (!cmdIdentify()) { Serial.println("FAIL identify"); return false; }

if (!cmdConfigRead()) { Serial.println("FAIL configRead"); return false; }

if (!cmdKeyGenerate(60)) { Serial.println("FAIL keygen"); return false; }

const uint32_t sectors = (fwLen + 1023u) / 1024u;

Serial.print("Erasing "); Serial.print(sectors); Serial.println(" sectors (1K)...");

if (!cmdFlashErase(sectors)) { Serial.println("FAIL erase"); return false; }

Serial.println("Writing...");

for (uint32_t off = 0; off < fwLen; off += (uint32_t)CHUNK_SIZE) {

uint16_t n = (uint16_t)min((uint32_t)CHUNK_SIZE, fwLen - off);

if (!cmdFlashWriteChunk(off, &fw[off], n)) {

Serial.print("FAIL write @"); Serial.println(off);

return false;

}

}

if (!cmdFlashWriteFinalize(fwLen)) { Serial.println("FAIL write finalize"); return false; }

if (verify) {

if (!cmdKeyGenerate(60)) { Serial.println("FAIL keygen2"); return false; }

Serial.println("Verifying...");

for (uint32_t off = 0; off < fwLen; off += (uint32_t)CHUNK_SIZE) {

uint16_t n = (uint16_t)min((uint32_t)CHUNK_SIZE, fwLen - off);

if (!cmdFlashVerifyChunk(off, &fw[off], n)) {

Serial.print("FAIL verify @"); Serial.println(off);

return false;

}

}

}

if (!cmdEnd(true)) { Serial.println("WARN end/reset failed"); }

Serial.println("DONE (resetting into user app)");

return true;

}

void setup() {

Serial.begin(HOST_BAUD);

delay(200);

pinMode(PIN_BOOT0, OUTPUT);

pinMode(PIN_NRST, OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(PIN_BOOT0, LOW);

digitalWrite(PIN_NRST, HIGH);

Serial1.setTX(PIN_UART_TX);

Serial1.setRX(PIN_UART_RX);

Serial1.begin(TARGET_BAUD);

rngState ^= micros();

Serial.println("Pico CH32 ISP ready.");

Serial.println("Commands: I=identify, C=config, F=flash+verify, f=flash, R=reset app");

}

void loop() {

if (!Serial.available()) return;

char c = (char)Serial.read();

if (c == 'I') {

Serial.println(cmdIdentify() ? "OK" : "FAIL");

} else if (c == 'C') {

bool ok = cmdIdentify() && cmdConfigRead();

Serial.println(ok ? "OK" : "FAIL");

} else if (c == 'F') {

(void)programEmbedded(true);

} else if (c == 'f') {

(void)programEmbedded(false);

} else if (c == 'R') {

runUserApp();

Serial.println("Reset into user app.");

}

}

After uploading the new firmware for the CH32 with a Pico, I have verification that this just might work. I can program the microcontrollers of a hypercube, so it’s time to build a hypercube.

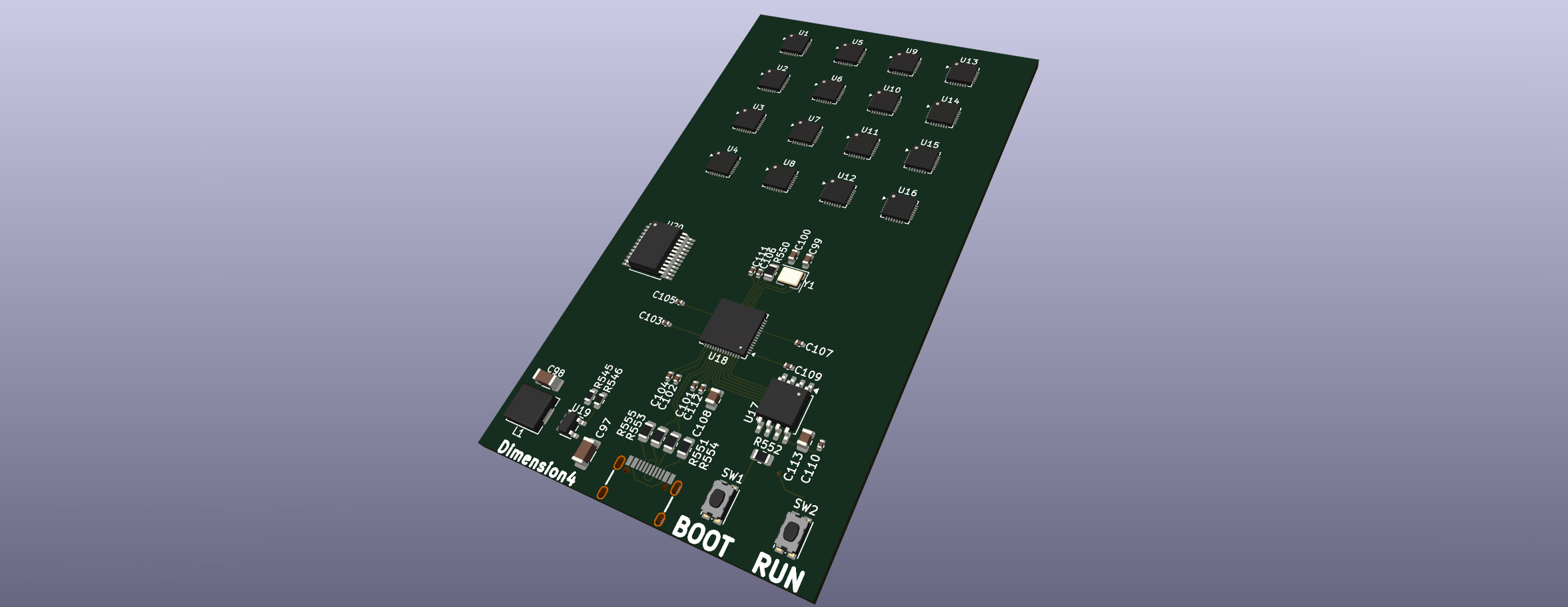

16 Nodes, The Slice

A more complete build log for the 16 node prototype is available here

This is where the build starts getting serious. The purpose of the 16-node prototype is to verify the previous work of the 1-node build (programming via UART, external clocking) as well as defining the links between nodes, synchronization, and message passing between nodes. This is hard, and it’s a good idea to do this on a prototype board before scaling up to larger builds.

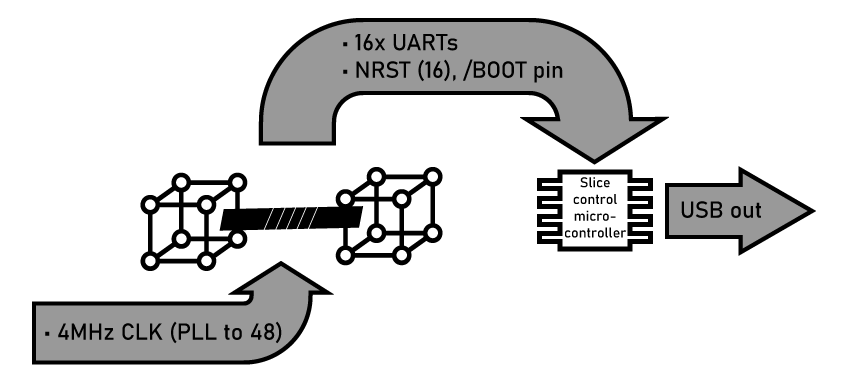

The Slice is a 4-dimensional hypercube, or 16 microcontrollers, each connected to 4 others. These 16 nodes are controlled by a dedicated microcontroller, programming each node over serial, toggling the reset circuit, and loading data into and out of each node.

The dedicated microcontroller used for this board is the RP2040. I’m using this chip for a few reasons. First, the PIOs. The PIOs in the RP2040 are small state machines that have access to GPIOs and memory via DMA that run independently of the core. I have used this functionality before to generate clock signals and read data directly into memory, as well as controlling the I2C lines in the LED panel. The PIOs are fantastic little peripherals that enable me to program a clock sent to all of the ‘Slice’ microcontrollers and read serial output. It’s a lot easier and cheaper than finding a microcontroller with 16 independent UARTs, too.

Hypercube Communication

The 16-node board is also the first experiment with the hypercube links between nodes. Simply because I don’t want double the work and density of wires in the full machine, I’m using a single wire communication between the nodes, just connecting one GPIO pin of a node to another GPIO pin of another node. These are single-wire half-duplex links, not a TX/RX pair. The CH32V203 only has two hardware UARTs, and one is dedicated to the Slice controller. If I need twelve UARTs for the hypercube connections, I’ll have to bitbang them in software.

The astute reader will notice many problems with twelve bit-banged UARTs over a single-wire open-drain connection between microcontrollers. Those are electrical engineering terms, so here’s automotive terms: it’s like doing the Baja 1000 in a stock 1993 Ford Taurus. Yeah, you can finish it, but you’re not making it easy on yourself. Back to electrical terms, you should really have two wires between chips, either as a Tx/Rx pair, or a data clock line pair. It would be really cool if you could use hardware UARTs if only to make programming simpler. But this is a hypercube computer, a single-wire link between nodes already means there are too many wires on the PCB, and I can’t find a single microcontroller with twelve UARTs.

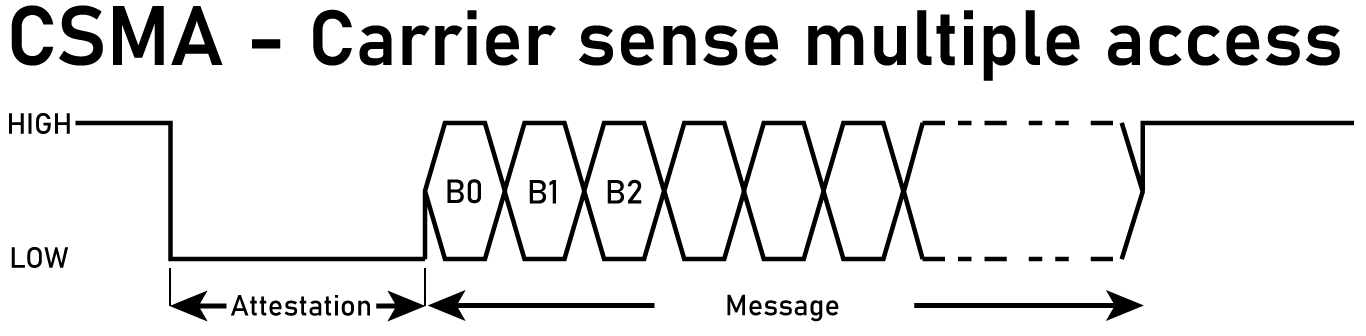

To actually pass messages back and forth between nodes through the hypercube array, we need a way to arbitrate the connections – which node actually gets to use the connection. There are several ways to do this.

CSMA vs TDMA

CSMA:

The naive way to arbitrate message passing between nodes is carrier-sense multiple access, or CSMA. Consider two nodes. At rest, the line is pulled high, because of the pullup. For node Alice to talk to node Bob, Alice first pulls the line low for some number of microseconds. Bob detects the line is low, and starts listening. Then Alice starts sending data. If Bob wants to talk to Alice, Bob pulls the line low, waits, then sends data. Alice listens.

This has significant drawbacks. There will be collisions, where both nodes want to talk at the same time. I would have to add backoff timers and retries, and god forbid acknowledgements. The code to do this is gnarly, and I simply don’t want to do it. Because there’s a better way.

TDMA:

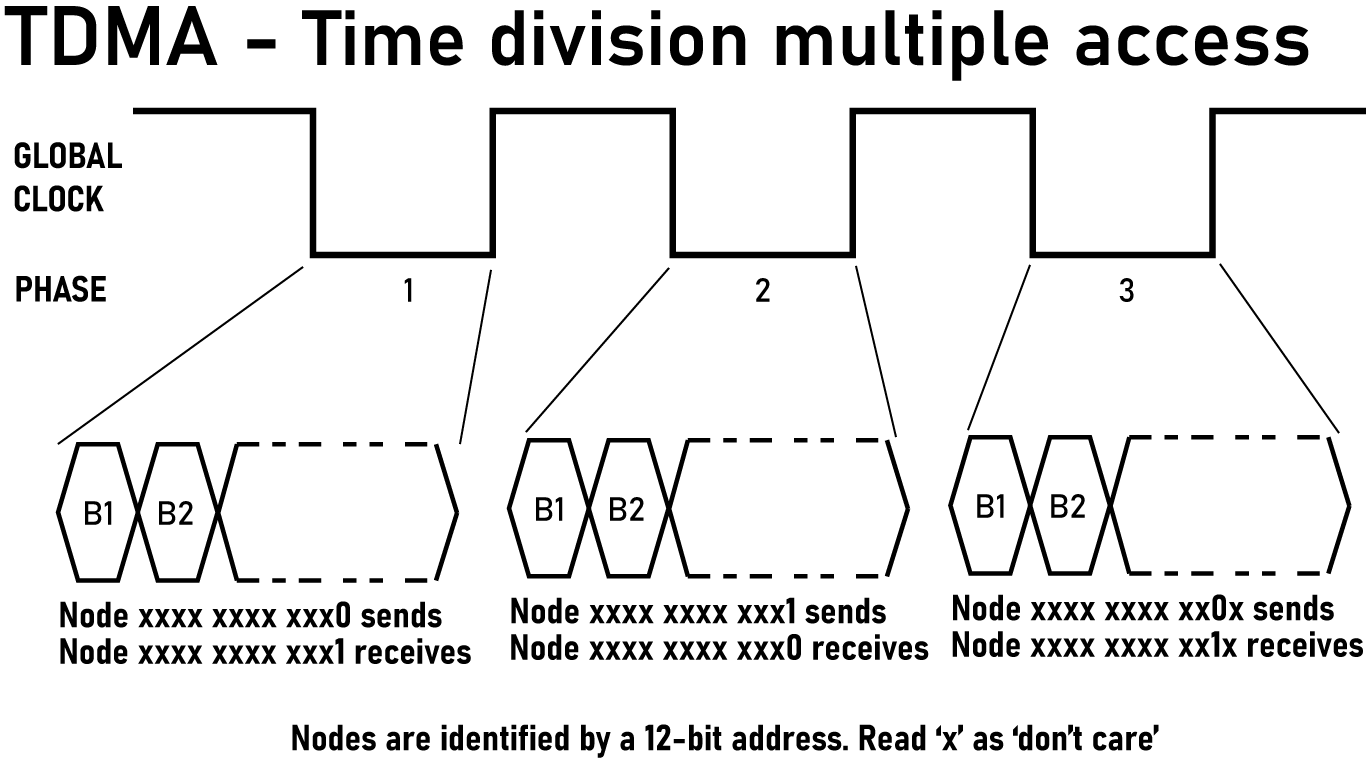

A more thorough explanation of the TDMA messaging scheme is available here

Consider the actual topology of what’s communicating here. All nodes are assigned a 12-bit number. Each connection is to a processor that is a single bit flip away. Node 0x2A3 is connected to node 0x2A2 (bit 0 flipped), node 0x2A1 (bit 1 flipped), node 0x2AB (bit 3 flipped), and so on.

Now define a global tick counter, synchronized across all nodes via the shared clock from the slice controllers. The phase is just tick mod 24 - twelve dimensions, two directions each. In phase d, only dimension d links are active. All other links stay idle. Within that phase, the node with addr[d] == 0 transmits first, then the node with addr[d] == 1 transmits in the second half. This is time-division multiple access, or TDMA.

Or, if you prefer text form:

- Phase 0: Nodes with address

xxxx xxxx xxx0sends → Nodesxxxx xxxx xxx1receives - Phase 1: Nodes with address

xxxx xxxx xxx1sends → Nodesxxxx xxxx xxx0receives - Phase 2: Nodes with address

xxxx xxxx xx0xsends → Nodesxxxx xxxx xx1xreceives - Phase 3: Nodes with address

xxxx xxxx xx1xsends → Nodesxxxx xxxx xx0xreceives - Phase 4: Nodes with address

xxxx xxxx x0xxsends → Nodesxxxx xxxx x1xxreceives - Phase 5: Nodes with address

xxxx xxxx x1xxsends → Nodesxxxx xxxx x0xxreceives - And so on for 24 phases…

The brilliant part about this is that no node ever talks to its neighbor at the same time. Collisions are impossible, and this scheme vastly simplifies the UART code for each node. In fact, because only dimension connection is active at any one time, I ONLY NEED ONE UART FOR THE HYPERCUBE, reconfigured for different pins for each phase.

Since only one dimension is active per phase, each node only needs to speak on one physical link at a time. If the UART can be remapped fast enough, one hardware UART can time-multiplex across all 12 links. The hypercube unfolds into time. Twelve dimensions become twenty-four phases, and the topology is temporal as much as spatial. Now we have a counter to the redditor who will say, “well acktually it’s not a true hypercube because we live in four dimensions, three spacial dimension plus time.” We can now tell that loser to stuff it.

It’s also fast:

Throughput at various baud rates:

| Baud Rate | Per-Link BW | Per-Node BW | Machine Aggregate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 115.2 kbps | 4.8 kbps | 115.2 kbps | 236 Mbps |

| 500 kbps | 20.8 kbps | 500 kbps | 1.02 Gbps |

| 1 Mbps | 41.7 kbps | 1 Mbps | 2.05 Gbps |

| 2 Mbps | 83.3 kbps | 2 Mbps | 4.1 Gbps |

Latency at various phase rates:

| Phase Rate | Phase Duration | Bits per Phase @ 1Mbps | 12-Hop Latency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 kHz | 1 ms | 1000 bits | 144 ms |

| 10 kHz | 100 µs | 100 bits | 14.4 ms |

| 100 kHz | 10 µs | 10 bits | 1.44 ms |

| 1 MHz | 1 µs | 1 bit | 144 µs |

There’s a catch with this plan

As discussed above, most chips, including the CH32V203, can not assign UART functions to any pin. The CH32V203 does not have this pin remapping function. The AG32VF-ASIC from AGM Micro can do this. This chip is a RISC-V RV32IMAFC microcontroller bolted onto a CPLD with 2K LUTs. All peripheral functions can be mapped onto any pin, and this can be done dynamically. It’s eighty cents a piece on LCSC.

This is actually going to work And with TDMA, 16-node prototype verifies everything needed for the full 4096-node machine. If TDMA works with 16 nodes, it’ll work with 4096.

I want to take a step back here and just point out I’m designing a machine that can move a gigabit or more per second around its memory, does this with a single hardware UART, and is built out of thirty cent RISC-V microcontrollers. All of this just falls out of the topology of the machine. Instead of a furball of code trying to get rid of problems with carrier sense, TDMA based on the address of the node solves the problem elegantly.

This should be your first realization that the hypercube architecture is recursively elegant. If you construct a parallel computer with a hypercube architecture, cool stuff just appears.

Two documents were created to explain the 16 node prototype, linked here:

Related pages:

256 Nodes, The Plane

The 256 node prototype builds on the progress made with the 1-node and 16-node boards. It is effectively sixteen copies of the 16-node board, with an additional Plane controller chip talking to each of the 16 Slice controllers. This prototype is effectively also the first ‘production’ circuit; in the full machine, I’m splitting up 4096 nodes over 16 individual boards of 256 nodes. This means the 256 node prototype is also the first revision of the main processor boards that will go into the machine.

The 256 node board is also the first one prototype where things get really hairy and interesting. Each chip is connected to eight other chips in the hypercube array. For 256 chips, this means there are 2048 inter-node links. If the chips can handle this, they’re probably good for the entire 4096-node full machine.

4096 Nodes

This is where the magic happens. The original CM-1 was controlled via a DEC VAX or Lisp machine that acted as a front-end processor. The front-end would broadcast instructions to the array, collect results, and handle I/O with the outside world. My machine needs something similar. At the top of the hierarchy sits a Zynq SoC - an FPGA with ARM cores bolted on. This is the easiest way to get

This handles:

- Instruction broadcast: In SIMD mode, the Zynq sends opcodes down the tree to all 4,096 nodes simultaneously

- Result aggregation: Data flows up through the Planes, gets collected, and presents to the outside world

- Network interface: Ethernet to everything else, USB, and HDMI simply because the Zynq support it. It’s a Linux machine, after all.

- LED coordination: Someone has to tell that 64x64 array what to display

The Zynq talks to 16 Plane controllers. Each Plane controller talks to 16 Slice controllers. Each Slice controller talks to 16 nodes. It’s trees all the way down.

The Backplane

The backplane is the key to the entire machine. This is historically true for big, old machines. I’ve been inside a PDP Straight-8, and the entire computer is composed of small cards containing just a few circuits. Plug them into the backplane – a gigantic wire-wrapped monstrosity – and the computer appears out of these simple single-circuit cards. The Cray Couch, despite vastly more complicated modules, appears when you add miles of wire in between these modules. This machine is no exception.

The modular nature of my machine means I only have to design one processor board and manufacture it 16 times. Each board handles 2,048 internal connections between its 256 chips, and exposes 1,024 connections to the backplane. The backplane does all the heavy lifting. It’s where the real routing complexity lives, implementing the inter-board connections that make 16 separate 8D cubes behave like one unified 12D hypercube. The boards are segmented like this:

Board-to-Board Connection Matrix

Rows = Source Board, Columns = Destination Board, Values = Number of connections

| Board | B00 | B01 | B02 | B03 | B04 | B05 | B06 | B07 | B08 | B09 | B10 | B11 | B12 | B13 | B14 | B15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B00 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B01 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B02 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B03 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B04 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B05 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 |

| B06 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 |

| B07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 |

| B08 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B09 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 |

| B10 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 |

| B11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 |

| B12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 |

| B13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 |

| B14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 256 |

| B15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 256 | 0 | 256 | 256 | 0 |

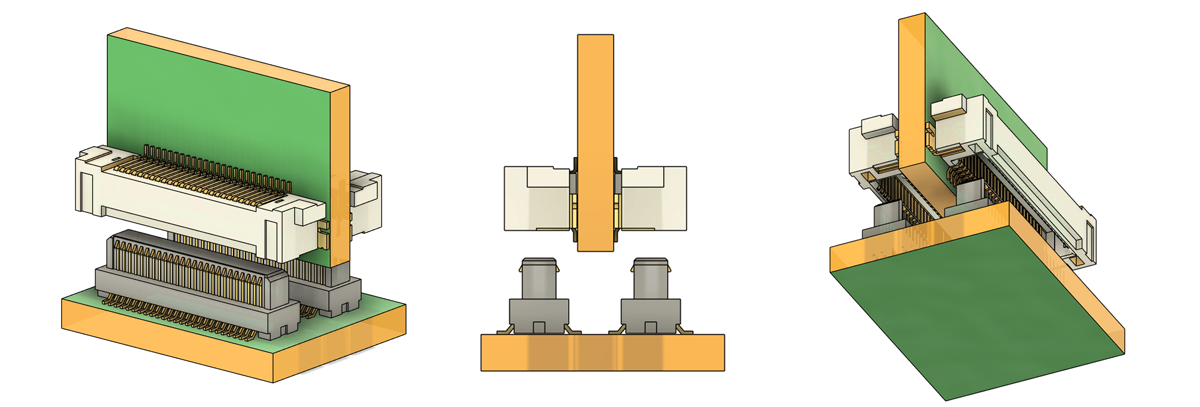

The Backplane Connectors

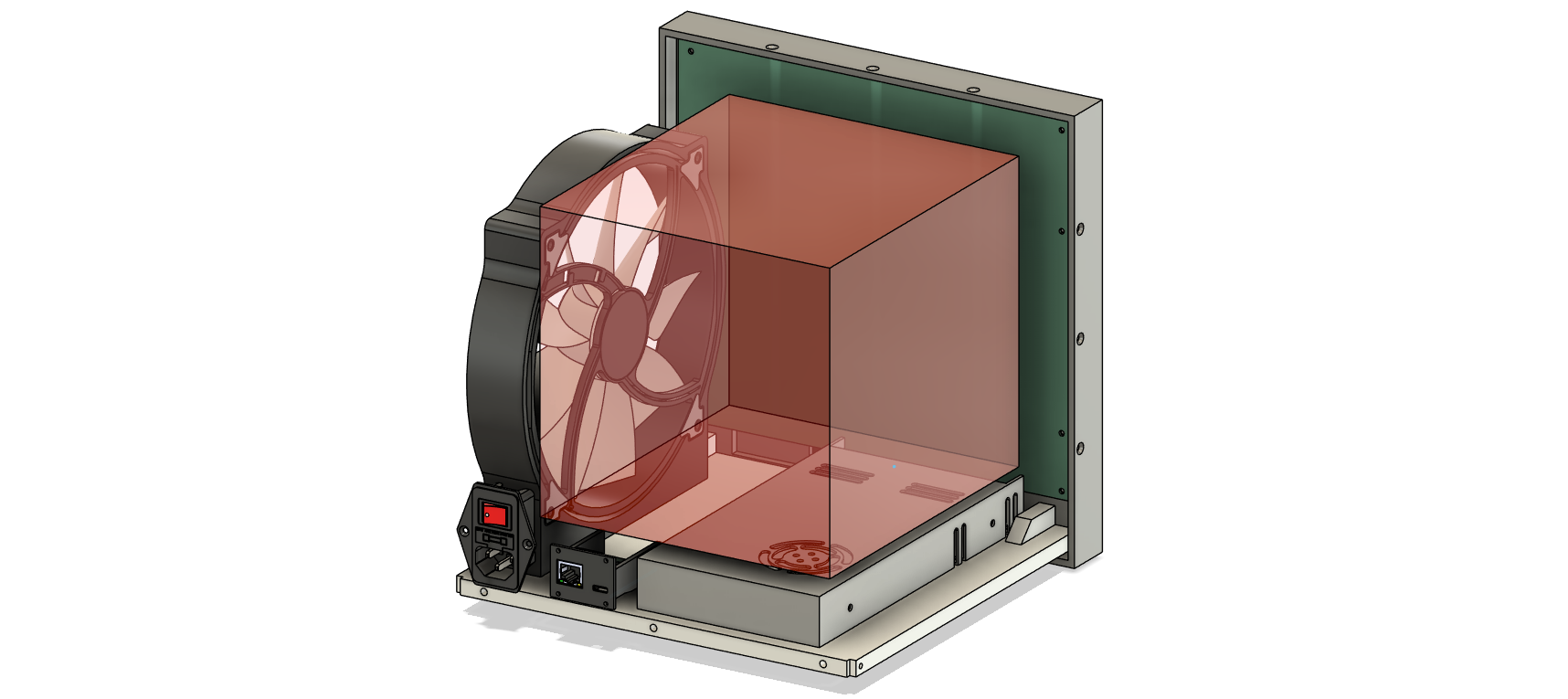

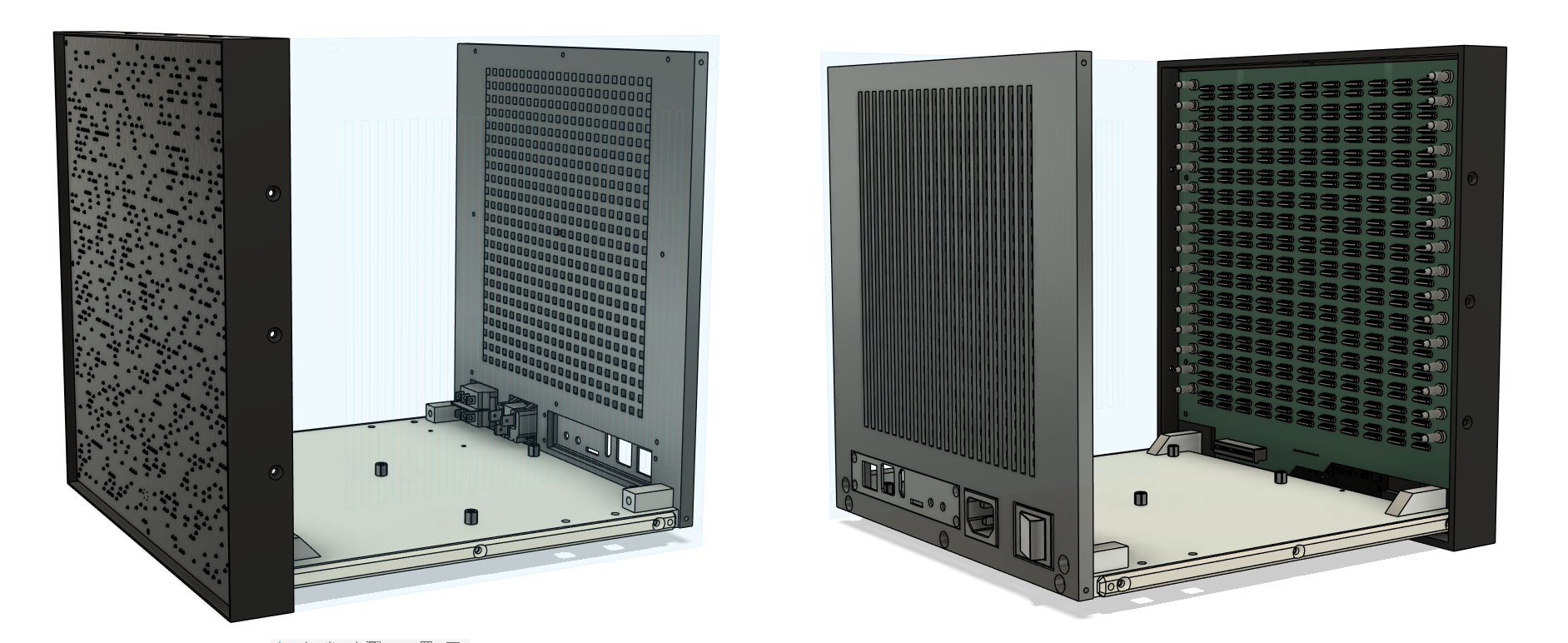

Mechanically, this device is tight. The LED panel is screwed into a frame that also holds the back plane on the opposite side. The back side has USB-C and Ethernet connections to the outside world. Internally, there’s a bunch of crap. A Mean Well power supply provides the box with 12V power. Since 4096 RISC-V chips will draw hundreds of Watts, cooling is also a necessity. A quartet of fans are bolted to the back panel of the device. Noctua on that thang.

There’s a lot of stuff in this box, and not a lot of places to put 16 boards. Here’s a graphic showing the internals of the device, with the area for the RISC-V boards highlighted in pink:

There isn’t much space to put the connectors for sixteen boards, especially connectors with 1100 pins. Dividing 1100 pins by the available length of 200mm gives us a pin pitch of 0.2mm. The pins for the connectors would have to be 0.2mm apart. This just doesn’t exist.

So how do you physically connect 1024 signals per board, in 200mm, with 10mm of height to work with? You don’t, because the connector you need doesn’t exist. After an evening spent crawling Samtec, Amphenol, Hirose, and Molex catalogs, I landed on this solution:

For the card-to-backplane connections, I’m using Molex SlimStack connectors, 0.4mm pitch, dual row, with 50 circuits per connector. They are Part Number 5033765020 for the right angle connectors on each card, and Part Number 545525010 for the connectors on the backplane. Instead of using a single connector on one side of the cards, I’m doubling it up, with connectors on both the top and the bottom. Effectively, I’m creating my own 4-row right angle SMT connector. Obviously, the connectors are also doubled on the backplane. This gives me 100 circuits in just 15mm of width along the ‘active’ edge of each card, and a card ‘pitch’ of 8mm. This is well within the requirements of this project. It’s insane, but everything about this project is.

With an array of 22 connectors per card – 11 on both top and bottom – I have 1100 electrical connections between the cards and backplane, enough for the 1024 hypercube connections, and enough left over for power, ground, and some sparse signalling. That’s the electrical connections sorted, but there’s still a slight mechanical issue. For interfacing and mating with the backplane, I’ll be using Samtec’s GPSK guide post sockets and GPPK guide posts. With that, I’ve effectively solved making the biggest backplane any one person has ever produced.

Above is a render of the machine showing the scale and density of what’s going on. Most of the front of the computer is the backplane, with the ‘compute cards’ – sixteen of the 8-dimensional hypercube boards – filling all the space. The cards, conveniently, are on a half-inch pitch, or 0.5 inches from card to card.

It’s tight, but it’s possible. The rest is only a routing problem.

The Backplane Schematic

This script defines the links between nodes in a 12D hypercube, broken up into 16 8D cubes:

import sys

import random

import math

import copy

def generate_board_routing(num_boards, output_file="hypercube_routing.txt"):

nodes_per_board = 256 # 8D cube per board

total_nodes = num_boards * nodes_per_board

total_dimensions = 12 # 12D hypercube

# Define which dimensions are on-board vs off-board

onboard_dims = list(range(8)) # Dimensions 0-7 are within each board

offboard_dims = list(range(8, 12)) # Dimensions 8-11 connect between boards

if num_boards != 2 ** (total_dimensions - 8):

print(f"Warning: For a full 12D cube with 8D boards, you need {2 ** (total_dimensions - 8)} boards.")

# Initialize data structures

boards = {board_id: {"local": [], "offboard": [], "local_count": 0, "offboard_count": 0} for board_id in range(num_boards)}

connection_matrix = [[0 for _ in range(num_boards)] for _ in range(num_boards)]

for node in range(total_nodes):

board_id = node // nodes_per_board

local_conns = []

offboard_conns = []

# Handle on-board connections (dimensions 0-7)

for d in onboard_dims:

neighbor = node ^ (1 << d)

if neighbor < total_nodes:

neighbor_board = neighbor // nodes_per_board

if neighbor_board == board_id: # Should always be true for dims 0-7

local_conns.append(neighbor)

boards[board_id]["local_count"] += 1

# Handle off-board connections (dimensions 8-11)

for d in offboard_dims:

neighbor = node ^ (1 << d)

if neighbor < total_nodes:

neighbor_board = neighbor // nodes_per_board

if neighbor_board != board_id: # Should always be true for dims 8-11

offboard_conns.append((neighbor, d))

boards[board_id]["offboard_count"] += 1

connection_matrix[board_id][neighbor_board] += 1

boards[board_id]["local"].append((node, local_conns))

boards[board_id]["offboard"].append((node, offboard_conns))

# Perform placement optimization

grid_size = num_boards

original_mapping = list(range(num_boards)) # Board ID to grid position

optimized_mapping = simulated_annealing(connection_matrix, grid_size)

inverse_mapping = {new_id: old_id for new_id, old_id in enumerate(optimized_mapping)}

# Output routing

with open(output_file, "w") as f:

f.write(f"=== Hypercube Routing Analysis ===\n")

f.write(f"Total nodes: {total_nodes}\n")

f.write(f"Nodes per board: {nodes_per_board}\n")

f.write(f"Number of boards: {num_boards}\n")

f.write(f"On-board dimensions: {onboard_dims}\n")

f.write(f"Off-board dimensions: {offboard_dims}\n\n")

for board_id in range(num_boards):

f.write(f"\n=== Board {board_id} ===\n")

f.write("Local connections (dimensions 0-7):\n")

for node, local in boards[board_id]["local"]:

if local: # Only show nodes that have local connections

f.write(f"Node {node:04d}: {', '.join(str(n) for n in local)}\n")

f.write("\nOff-board connections (dimensions 8-11):\n")

for node, offboard in boards[board_id]["offboard"]:

if offboard:

# Show which boards each node connects to, not the dimension

conns = []

for neighbor_node, d in offboard:

neighbor_board = neighbor_node // nodes_per_board

conns.append(f"(Node {neighbor_node} -> Board {neighbor_board:02d})")

conns_str = ', '.join(conns)

f.write(f"Node {node:04d}: {conns_str}\n")

f.write("\nSummary:\n")

f.write(f"Total local connections (on-board): {boards[board_id]['local_count']}\n")

f.write(f"Total off-board connections: {boards[board_id]['offboard_count']}\n")

# Output original board-to-board connection matrix

f.write("\n=== Original Board-to-Board Connection Matrix ===\n")

f.write("Rows = Source Board, Columns = Destination Board\n\n")

header = " " + "".join([f"B{b:02d} " for b in range(num_boards)]) + "\n"

f.write(header)

for i in range(num_boards):

row = f"B{i:02d}: " + " ".join(f"{connection_matrix[i][j]:3d}" for j in range(num_boards)) + "\n"

f.write(row)

# Verify the matrix matches expected pattern

f.write("\n=== Connection Matrix Verification ===\n")

for i in range(num_boards):

connected_boards = [j for j in range(num_boards) if connection_matrix[i][j] > 0]

f.write(f"Board {i} connects to boards: {connected_boards}\n")

# Each board should connect to exactly 4 other boards (for dims 8,9,10,11)

if len(connected_boards) != 4:

f.write(f" WARNING: Expected 4 connections, got {len(connected_boards)}\n")

# Output optimized board-to-board connection matrix

f.write("\n=== Optimized Board-to-Board Connection Matrix (Reordered Boards) ===\n")

f.write("Rows = New Source Board (Grid Order), Columns = New Destination Board\n\n")

f.write(header)

for i in range(num_boards):

real_i = optimized_mapping[i]

row = f"B{i:02d}: " + " ".join(f"{connection_matrix[real_i][optimized_mapping[j]]:3d}" for j in range(num_boards)) + "\n"

f.write(row)

# Output board-to-grid mapping

f.write("\n=== Board to Grid Mapping ===\n")

for idx, board_id in enumerate(optimized_mapping):

x, y = idx % grid_size, idx // grid_size

f.write(f"Grid Pos ({x}, {y}): Board {board_id}\n")

print(f"Board routing and connection matrix (optimized) written to {output_file}")

def compute_total_cost(mapping, connection_matrix, grid_size):

num_boards = len(mapping)

pos = {mapping[i]: i for i in range(num_boards)} # slot positions in 1D

cost = 0

for i in range(num_boards):

for j in range(num_boards):

if i != j:

distance = abs(pos[i] - pos[j])

cost += connection_matrix[i][j] * distance

return cost

def simulated_annealing(connection_matrix, grid_size, initial_temp=10000.0, final_temp=1.0, alpha=0.95, iterations=5000):

num_boards = len(connection_matrix)

current = list(range(num_boards))

best = current[:]

best_cost = compute_total_cost(best, connection_matrix, grid_size)

temp = initial_temp

for it in range(iterations):

# Random swap

i, j = random.sample(range(num_boards), 2)

new = current[:]

new[i], new[j] = new[j], new[i]

new_cost = compute_total_cost(new, connection_matrix, grid_size)

delta = new_cost - best_cost

if delta < 0 or random.random() < math.exp(-delta / temp):

current = new

if new_cost < best_cost:

best = new[:]

best_cost = new_cost

temp *= alpha

if temp < final_temp:

break

return best

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print("Usage: python generate_hypercube_routing.py <num_boards>")

sys.exit(1)

num_boards = int(sys.argv[1])

generate_board_routing(num_boards)

This script will spit out an 8000+ line text file, defining all 4096 nodes and all of the connections between nodes. For each of the 16 CPU boards, there are 2048 local connections to other chips on the same board, and 1024 off-board connections. The output of the above script looks like Node 2819: 2818, 2817, 2823, 2827, 2835, 2851, 2883, 2947, meaning Node 2819 connects to 8 other nodes locally. I also get the off-board connections with Node 2819: (Node 2563 -> Board 10), (Node 2307 -> Board 09), (Node 3843 -> Board 15), (Node 771 -> Board 03). Add these up, and you can get a complete list of what’s connected to this single node:

Node 2819 (on Board 11):

- Connected to 2818, 2817, 2823, 2827, 2835, 2851, 2883, 2947 locally

- Connected to 2563 on Board 10

- Connected to 2307 on Board 9

- Connected to 3843 on Board 15

- Connected to 771 on Board 3

That’s the complete routing. But I’m not doing a complete routing; this is going to be broken up over multiple boards and connected through a very very large backplane. This means even more scripting. For creating the backplane routing, I came up with this short script that generates a .CSV file laying out the board-to-board connections:

import csv

from collections import defaultdict

NUM_BOARDS = 16

NODES_PER_BOARD = 256

TOTAL_NODES = NUM_BOARDS * NODES_PER_BOARD

DIMENSIONS = 12

OFFBOARD_DIMS = [8, 9, 10, 11]

MAX_PINS_PER_CONNECTOR = 1024

def get_board(node_id):

return node_id // NODES_PER_BOARD

def get_node_on_board(node_id):

return node_id % NODES_PER_BOARD

def generate_offboard_connections():

# (board -> list of (local_node_id, dimension, neighbor_board, neighbor_node_id))

offboard_edges = []

for node in range(TOTAL_NODES):

for d in OFFBOARD_DIMS:

neighbor = node ^ (1 << d)

if neighbor >= TOTAL_NODES:

continue

b1 = get_board(node)

b2 = get_board(neighbor)

if b1 != b2:

offboard_edges.append((

(b1, get_node_on_board(node)),

d,

(b2, get_node_on_board(neighbor))

))

# De-duplicate (undirected)

seen = set()

deduped = []

for src, d, dst in offboard_edges:

net_id = tuple(sorted([src, dst]) + [d])

if net_id not in seen:

seen.add(net_id)

deduped.append((src, d, dst))

return deduped

def assign_pins(routing):

pin_usage = defaultdict(int) # board_id -> next free pin

pin_assignments = []

# Track connections per board pair for numbering

board_pair_signals = defaultdict(int)

for src, d, dst in routing:

b1, n1 = src

b2, n2 = dst

pin1 = pin_usage[b1] + 1

pin2 = pin_usage[b2] + 1

if pin1 > MAX_PINS_PER_CONNECTOR or pin2 > MAX_PINS_PER_CONNECTOR:

raise Exception(f"Ran out of pins on board {b1} or {b2}")

pin_usage[b1] += 1

pin_usage[b2] += 1

# Create short, meaningful net name

# Sort board numbers for consistent naming

if b1 < b2:

board_pair = (b1, b2)

signal_num = board_pair_signals[board_pair]

else:

board_pair = (b2, b1)

signal_num = board_pair_signals[board_pair]

board_pair_signals[board_pair] += 1

# Generate short net name: B00B01_042

net_name = f"B{board_pair[0]:02d}B{board_pair[1]:02d}_{signal_num:03d}"

pin_assignments.append((

net_name,

f"J{b1+1}", pin1,

f"J{b2+1}", pin2

))

return pin_assignments

def write_csv(pin_assignments, filename="backplane_routing.csv"):

with open(filename, "w", newline="") as csvfile:

writer = csv.writer(csvfile)

writer.writerow(["NetName", "ConnectorA", "PinA", "ConnectorB", "PinB"])

for row in pin_assignments:

writer.writerow(row)

print(f"Wrote routing to {filename}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Generating hypercube routing...")

routing = generate_offboard_connections()

print(f"Found {len(routing)} off-board connections.")

print("Assigning pins...")

pin_assignments = assign_pins(routing)

print("Writing CSV...")

write_csv(pin_assignments)

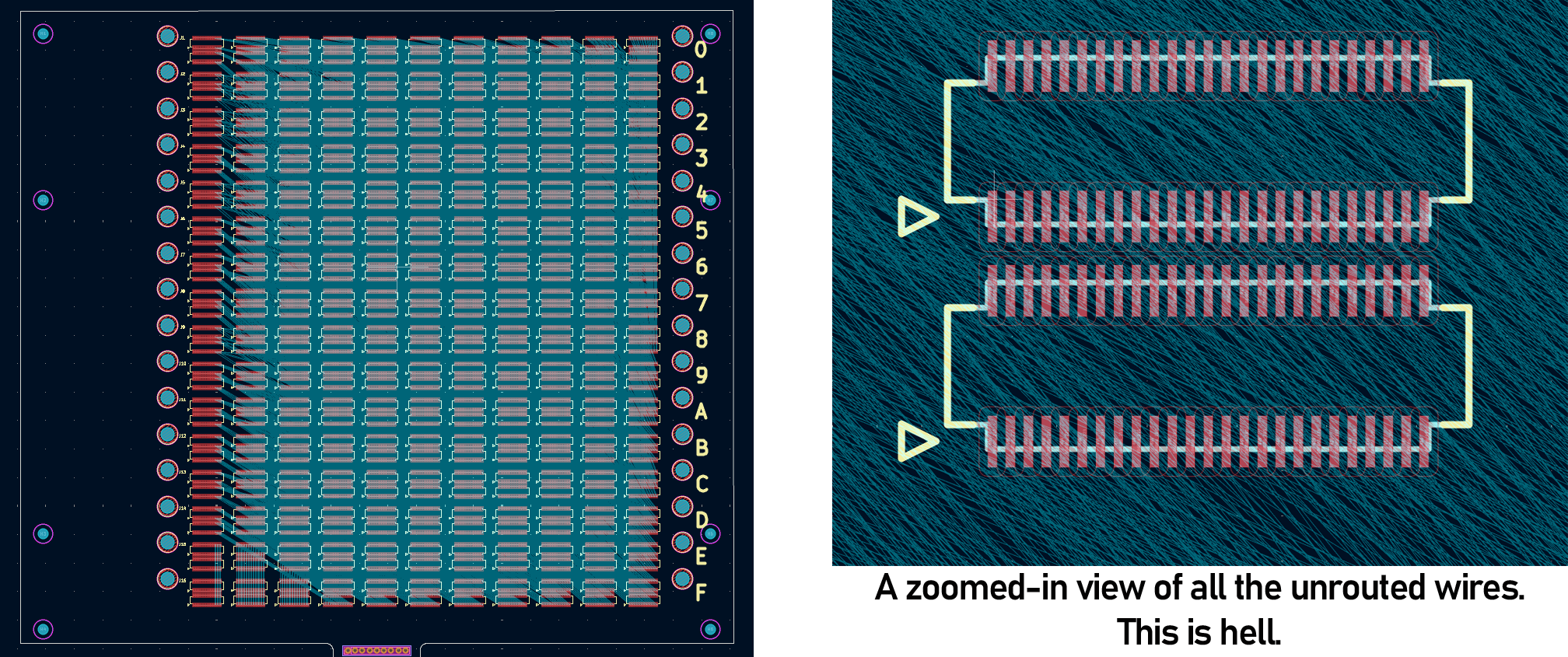

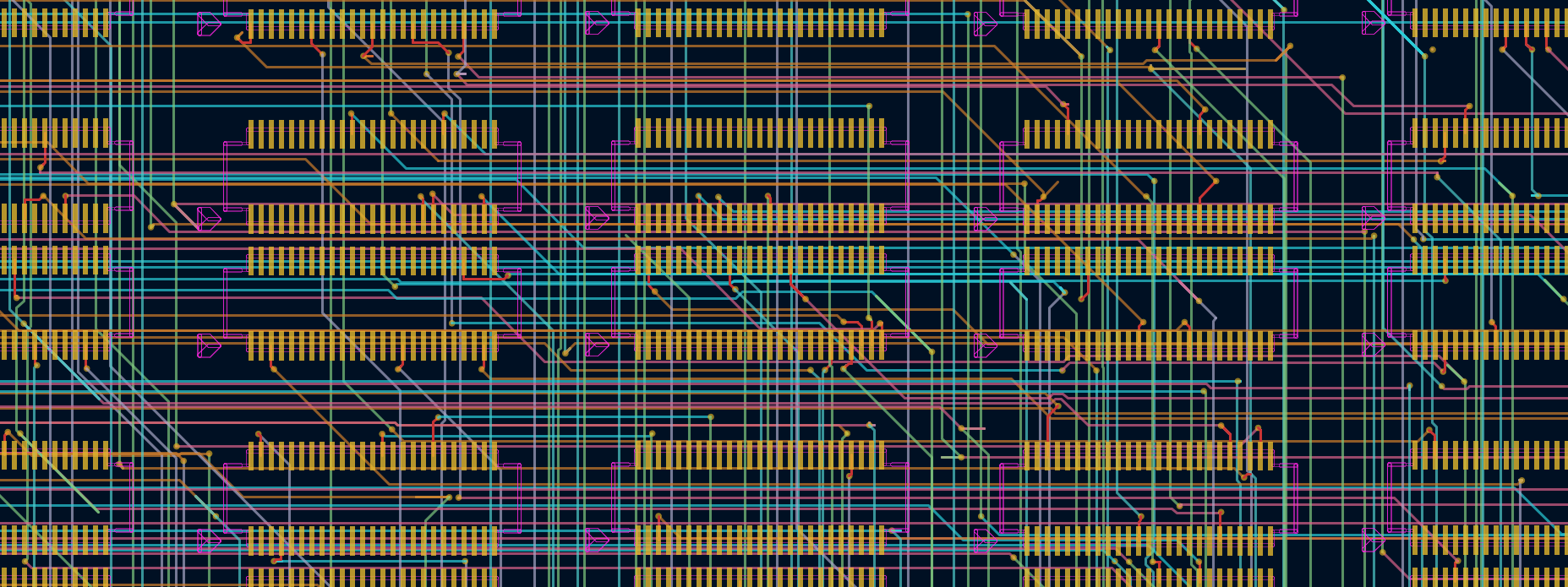

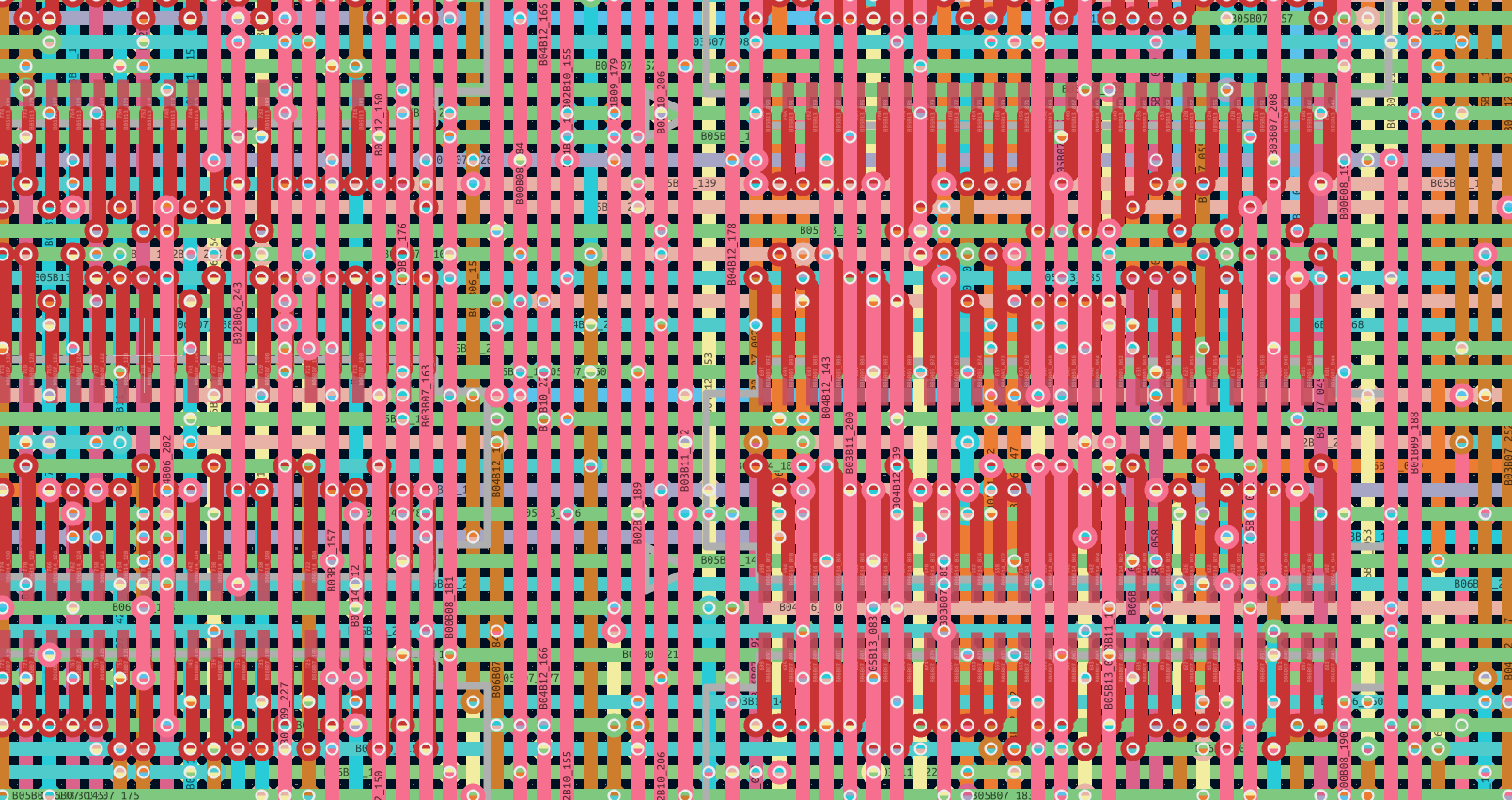

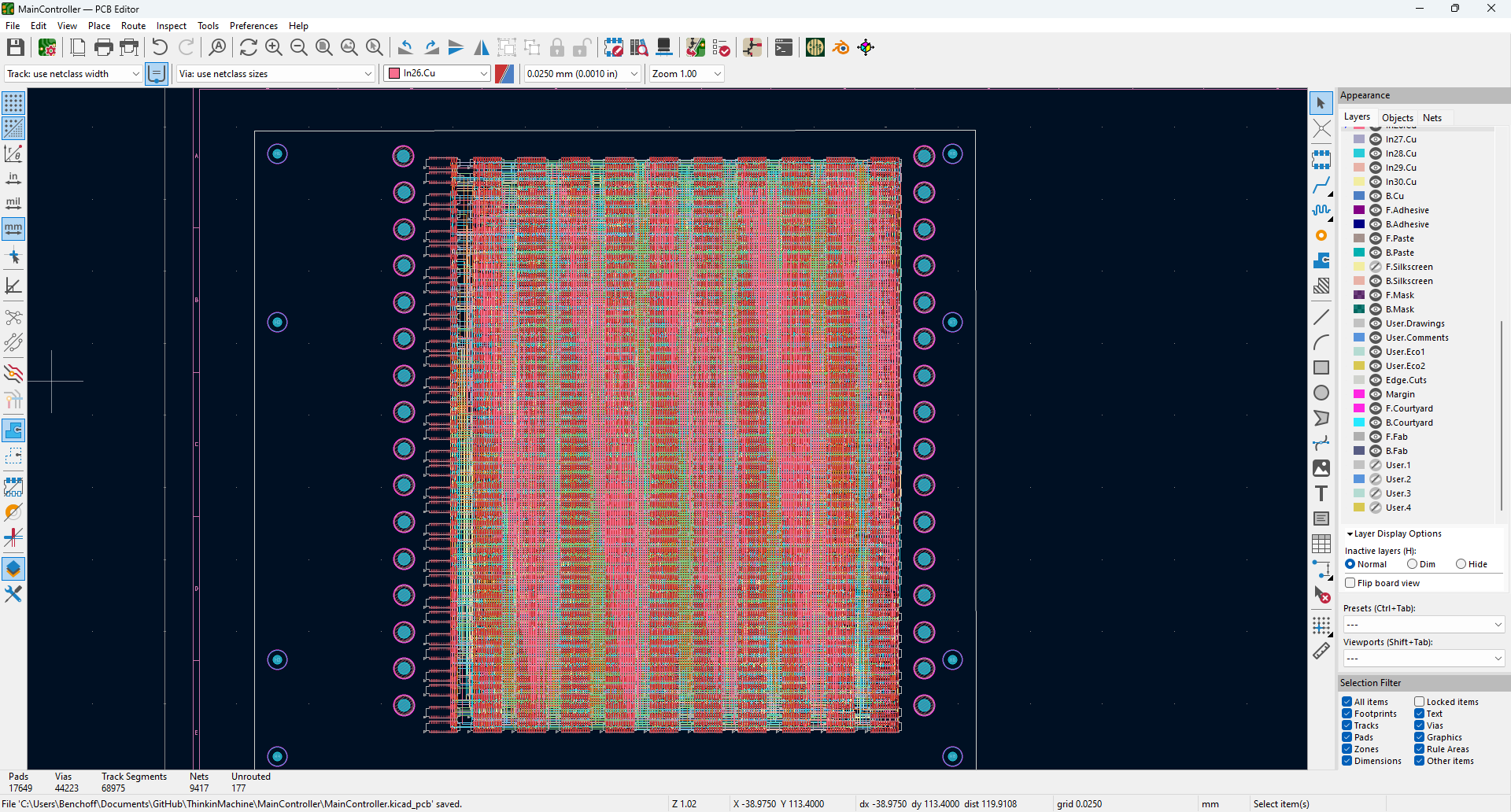

The output is just a netlist, and is an 8000-line file with lines that look like B10B11_246,J11,1005,J12,759. Here, the connection between Board 10 and Board 11, net 246, is defined as a connection between J11 (backplane connection number 11), pin 1005 and J12, pin 759. This was imported into the KiCad schematic with the kicad-skip library. The resulting schematic is just a little bit insane. It’s 16 connectors with 1100 pins each, and there are 8192 unrouted connections after importing the netlist.

Yeah, it’s the most complex PCB I’ve ever designed. Doing this by hand would take weeks. It’s also a perfect stress test for the autorouter. Using the FreeRouting plugin for KiCad, I loaded the board and set it to the task of routing 16,000 airwires with a 12-layer board. Here’s the result of seven hours of work, with 712 of those 16k traces routed:

These were the easy traces, too. It would have taken hundreds or thousands of hours for the autorouter to do everything, and it would still look like shit.

The obvious solution, therefore, is to build my own autorouter. Or at least spend a week or two on writing an autorouter.

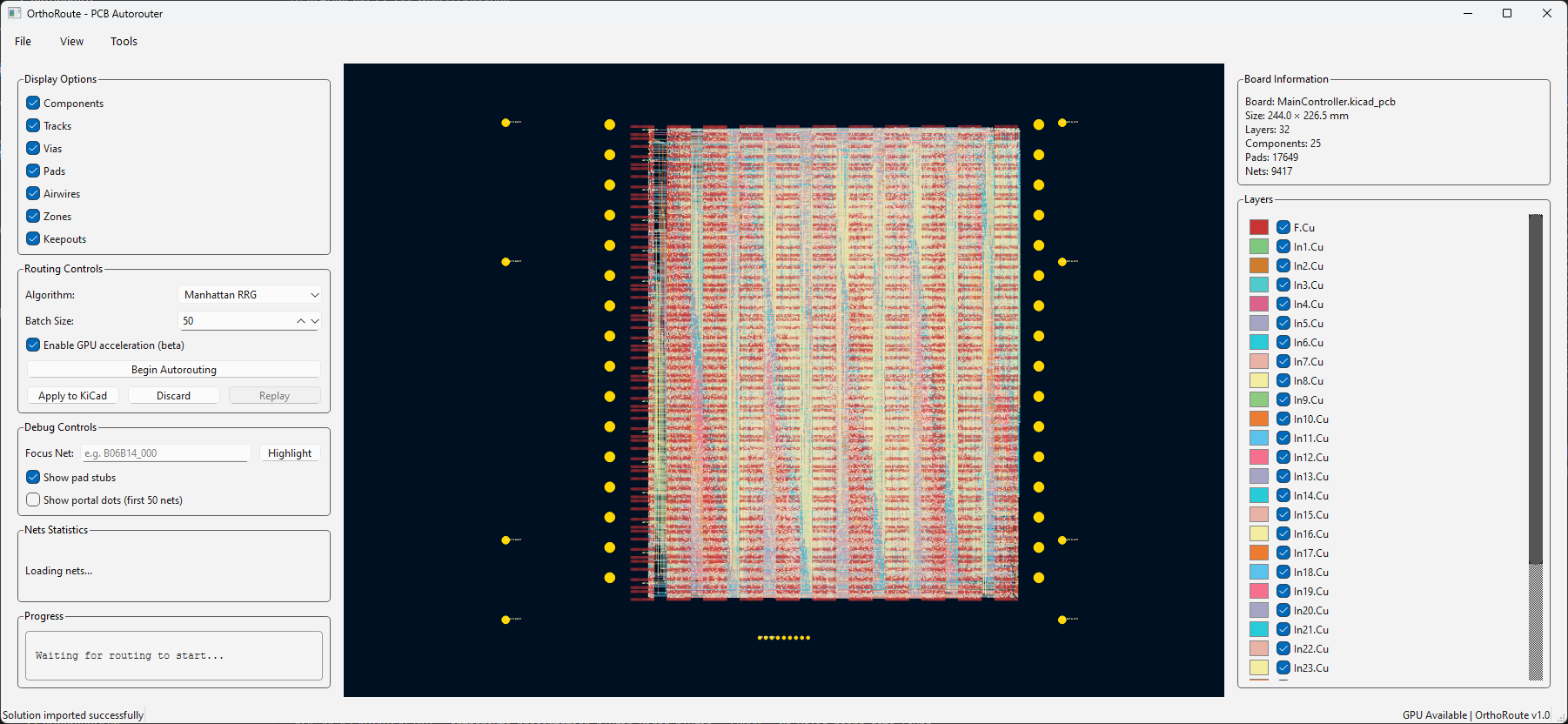

OrthoRoute

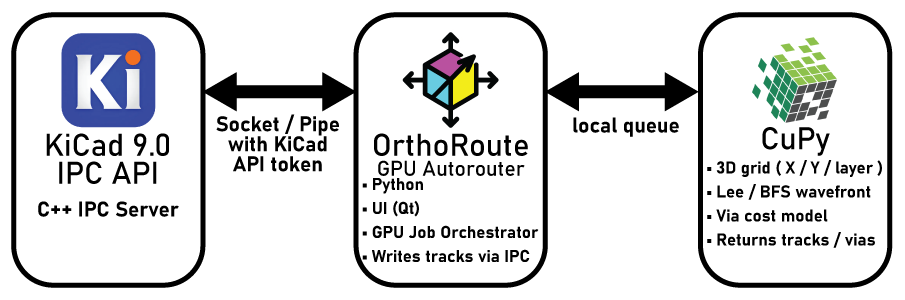

This is OrthoRoute, a GPU-accelerated autorouter for KiCad. There’s very little that’s actually new here; I’m just leafing through some of the VLSI books in my basement and stealing some ideas that look like they might work. If you throw enough compute at a problem, you might get something that works.

OrthoRoute is written for the new IPC plugin system for KiCad 9.0. This has several advantages over the old SWIG-based plugin system. IPC allows me to run code outside of KiCad’s Python environment. That’s important, since I’ll be using CuPy for CUDA acceleration and Qt to make the plugin look good. The basic structure of the OrthoRoute plugin looks something like this:

The OrthoRoute plugin communicates with KiCad via the IPC API over a Unix socket. This API is basically a bunch of C++ classes that gives me access to board data – nets, pads, copper pour geometry, airwires, and everything else. This allows me to build a second model of a PCB inside a Python script and model it however I want.

From there, OrthoRoute reads the airwires and nets and figures out what pads are connected together. This is the basis of any autorouter. OrthoRoute then uses CuPy and interesting algorithms ripped from the world of FPGA routing to turn a mess of airwires into a routed board.

The algorithm used for this autorouter is PathFinder: a negotiation-based performance-driven router for FPGAs. My implementation of PathFinder treats the PCB as a graph: nodes are intersections on an x–y grid where vias can go, and edges are the segments between intersections where copper traces can run. Each edge and node is treated as a shared resource.

PathFinder is iterative. In the first iteration, all nets (airwires) are routed greedily, without accounting for overuse of nodes or edges. Subsequent iterations account for congestion, increasing the “cost” of overused edges and ripping up the worst offenders to re-route them. Over time, the algorithm converges to a PCB layout where no edge or node is over-subscribed by multiple nets.

With this architecture – the PathFinder algorithm on a very large graph, within the same order of magnitude of the largest FPGAs – it makes sense to run the algorithm with GPU acceleration. There are a few factors that went into this decision:

- Everyone who’s routing giant backplanes probably has a gaming PC. Or you can rent a GPU from whatever company is advertising on MUNI bus stops this month.

- The PathFinder algorithm requires hundreds of billions of calculations for every iteration, making single-core CPU computation glacially slow.

- With CUDA, I can implement a SSSP (parallel Dijkstra) to find a path through a weighted graph very fast.

Note this is not a fully parallel autorouter; in OrthoRoute, nets are still routed in sequence on a shared congestion map. The parallelism lives inside the shortest-path search: a CUDA SSSP (“parallel Dijkstra”) kernel makes each individual net’s pathfinding fast, but it doesn’t route many nets simultaneously.

This yak is fuckin bald now. But I think the screencaps speak for themselves:

This board feels pain. You get mental damage from just looking at it. Every other board you’ve ever seen comes with the assumption that a human played some part in it. This does not; it’s purely an algorithm grinding away. It’s the worst board that you’ve ever seen.

You can run OrthoRoute yourself by downloading it from the repo. Install the .zip file via the package manager. A somewhat beefy Nvidia GPU is highly suggested but not required; there’s CPU fallback. If you want a deeper dive on how I built OrthoRoute, there’s also a page in my portfolio about it.

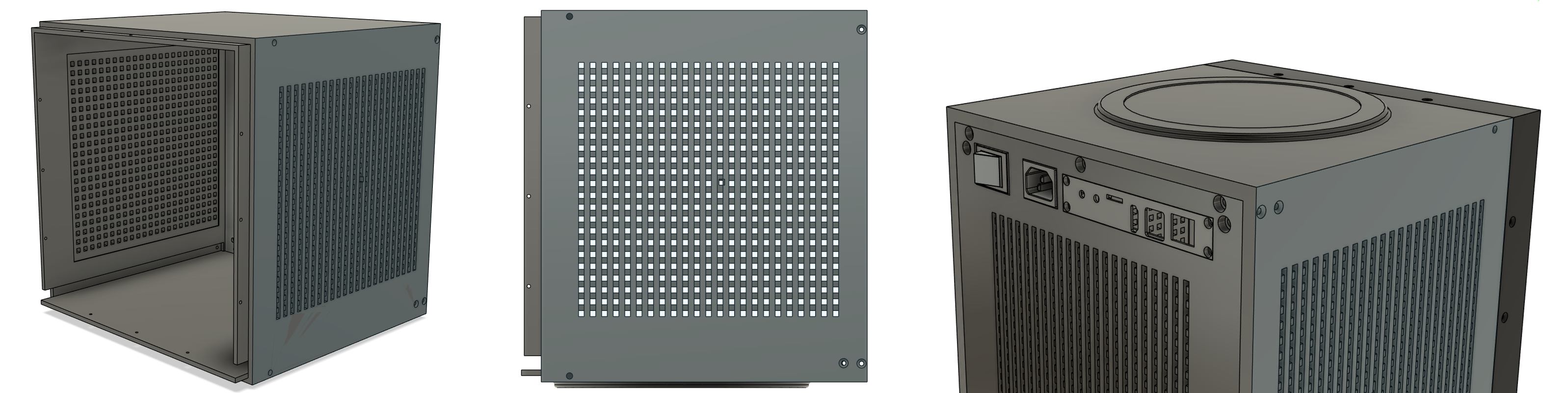

Mechanical Design

The entire thing is made out of machined aluminum plate. The largest and most complex single piece is the front – this holds the LED array, diffuser, and backplane. It attaches to the outer enclosure on all four sides with twelve screws. Attached to the front frame is the ‘base plate’ and the back side of the machine, forming one U-shaped enclosure. On the sides of the base plate are Delrin runners which slide into rabbets in the outer enclosure. This forms the machine’s chassis. This chassis slides into the outer enclosure.

The outer enclosure is composed of four aluminum plates, open on the front and back. The top panel is just a plate, and the bottom panel has a circular plinth to slightly levitate the entire machine a few millimeters above the surface it’s sitting on. The left and right panels have a grid pattern machined into them that is reminiscent of the original Connection Machine. These panels are made of 8mm plate, and were first screwed together, welded, then the screw holes plug welded. Finally, the enclosure was bead blasted and anodized matte black.

There is a small error in the grid pattern of one of the side pieces. Where most of the grid is 4mm squares, there is one opening that is irregular, offset by a few millimeters up and to the right. Somebody influential in the building of the Connection Machine once looked at the Yomeimon gate at Nikkō, noting that of all the figures carved in the gate, there was one tiny figure carved upside-down. The local mythology around this says it was done this way, ‘so the gods would not be jealous of the perfection of man’.

While my machine is really good, and even my guilt-addled upbringing doesn’t prevent me from taking some pride in it, I have to point out that I didn’t add this flaw to keep gods from being offended. I know this is not perfect. There is documentation on the original Connection Machine that I would have loved to reference, and there are implementations I would have loved to explore were time, space, and money not a consideration. The purposeful and obvious defect in my machine is simply saying that I know it’s not perfect. And this isn’t a one-to-one clone of the Connection Machine, anyway. It’s a little wabi-sabi saying forty years and Moore’s Law result in something that’s different, even if the influence is obvious.

Software Architecture

After building the hardware, with LED panels wrapped in Chemcast acrylic, plug welded aluminum frame, and a backplane that actually feels pain, you may wonder what this machine actually does. That’s a fair question. It’s elegant, beautiful, but it doesn’t really do anything useful. For many of us, that was an ex in our 20s. Now it’s a computer.

This machine is fundamentally incompatable with any programming language. The only way I have to program the 4,096 chips in the machine is through C, because that’s the toolchain I have. The real Connection Machine had a variety of languages like *Lisp, a parallel verison of Lisp, and C*, a parallel version of C. These languages don’t exist any more, insofar as I can find actual code. I can, however, look at sources and figure out how they were programmed in these languages.

C* and *Lisp and the parallel Fortran mentioned in an old NASA Ames publication all share the same basic ideas. The Connection Machine used parallel variables, where there’s one value per processor, scalar variables, which are the same value repeated on all the processors, and communication primitives like neighbor exchange, reduction, and broadcast. The languages are data-parallel, not message passing.

The problem is, there’s no existing language that does this. I can contort the C-based toolchain available for any microcontroller to do all this, but this is the sort of thing that should really be its own language, if only for error and type checking.

So I guess I have to create my own language for this computer.

StarC - Parallel C

This is StarC. It’s the language I had to write to make this machine programmable. There are three basic ideas that I’m adding to C:

Parallel variables. pvar<int> x means “every processor has its own x.” When you write x = x + 1, all 4,096 processors increment their local copy simultaneously.

Masked execution. where (x > 0) { ... } means “only processors where the condition is true execute this block.” The others skip it. This is how you express “some processors do this, others don’t” without breaking the single-program model.

Communication blocks. exchange { n = nbr(0, x); } means “every processor swaps its x with its dimension-0 neighbor.” All communication—neighbor exchange, grid neighbors, reductions, scans—happens inside exchange blocks. The runtime schedules it onto the TDMA phases. You declare what you need; the machine figures out when.

Here’s what StarC looks like in practice—a simple program that lights up processors based on their neighbors:

void main() {

pvar alive = (pid() % 7 == 0) ? 1 : 0; // Seed some processors

pvar neighbor;

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

exchange {

neighbor = nbr(0, alive); // Get dimension-0 neighbor's state

}

where (alive == 0 && neighbor == 1) {

alive = 1; // Dead processors with live neighbors come alive

}

led_set(alive * 255);

barrier();

}

}

Every processor runs this same code. Each has its own alive and neighbor. The exchange block swaps values with neighbors; the where block filters which processors update. The LED panel shows the result—a pattern spreading across the hypercube, one dimension at a time.

StarC Design

StarC is deliberately minimal. The language adds exactly three constructs to C: parallel variables, masked execution, and exchange blocks. StarC is a way to make illegal programs unrepresentable on a TDMA-scheduled hypercube. That’s what the hardware requires, and what C doesn’t natively provide. Everything else is still C.

Because we’re using a TDMA schedule to program this thing, costs should be visible. This is why exchange blocks exist as explicit syntax. The hardware batches all communication into TDMA phases—you can’t scatter nbr() calls throughout your code like function calls. Making exchange blocks syntactically distinct forces you to think about communication as a discrete step: compute, exchange, compute, exchange. The code structure mirrors the hardware’s rhythm.

The where/if distinction exists for the same reason. if with a scalar condition means all processors take the same branch. where with a parallel condition means processors diverge. Exchange blocks inside where are illegal; if half the processors skip an exchange, the TDMA schedule breaks. The preprocessor catches this at compile time rather than letting it fail mysteriously at runtime.

What StarC doesn’t have is equally deliberate. There’s no send(dest, msg) even though the TDMA scheme could support multi-hop routing. The interesting hypercube algorithms—bitonic sort, parallel prefix, stencils—don’t need it. Adding arbitrary routing would invite people to write programs the hardware executes poorly. StarC restricts you to what the hypercube does well.

You might be asking yourself, “wait, I’m smart and attractive and eminently capable and wealthy, why can’t I just implement these with macros?” You could, but StarC has rules that interact in ways macros can’t check. Exchange blocks can’t go inside where blocks, exchange results can’t be used as inputs in the same block, and if with a pvar is almost always a mistake. The preprocessor catches them at compile time instead.

StarC Infrastructure

For ‘production code’, StarC compiles to C via a Python preprocessor, which then gets shoved into whatever toolchain you’re using for whatever microcontroller. There’s no VM, and no crazy shit. This is the minimum possible tooling required to program a hypercube of microcontrollers.

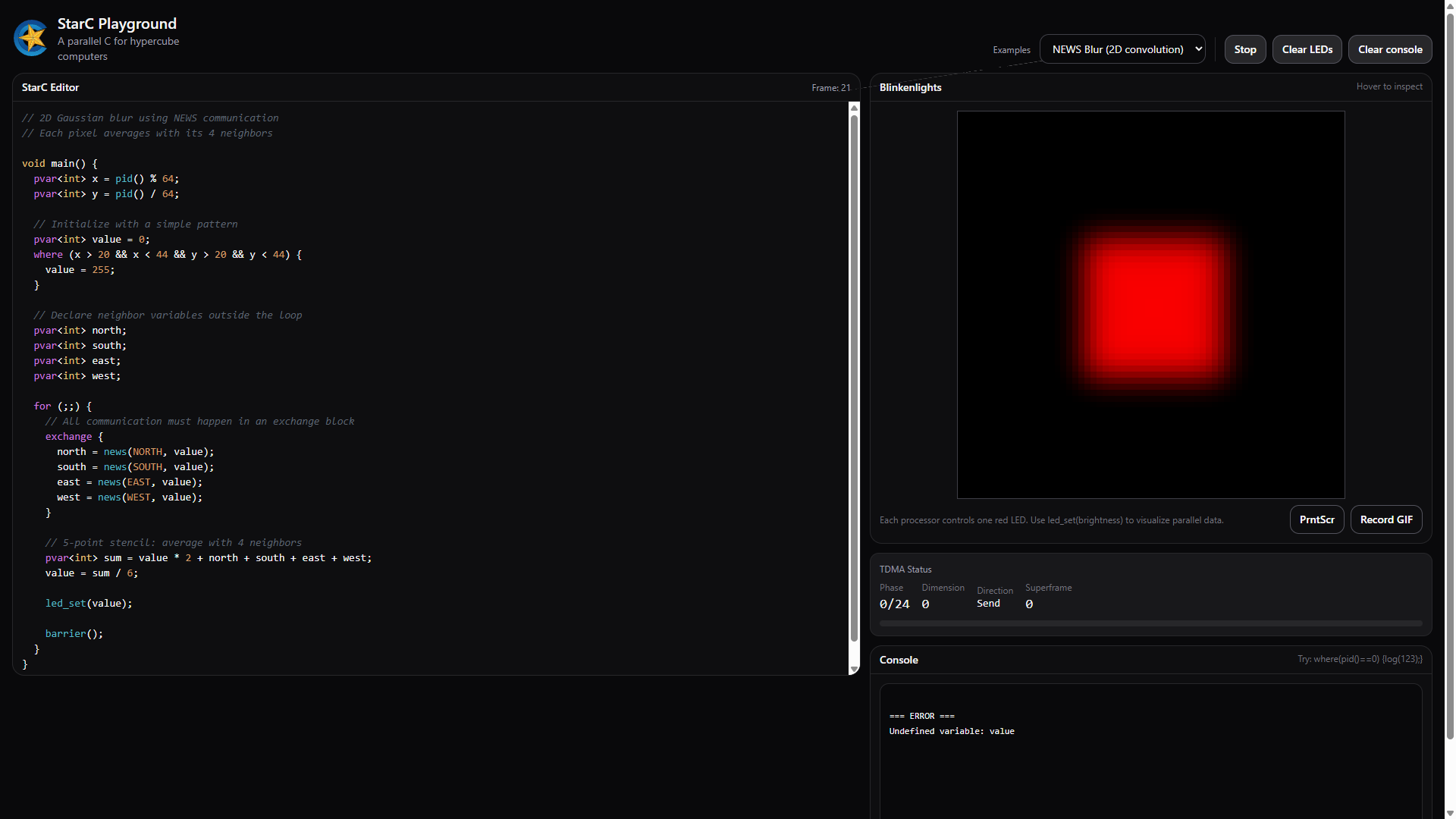

However, I had to design this language in parallel with building the machine. I needed a simulator, which means you also now have a simulator. Here’s the StarC Playground. It’s a React app with a tree-sitter parser using the C grammar, a JavaScript interpreter that runs 4,096 virtual processors, and a Canvas renderer for the LED panel. It’s not cycle-accurate, but it is logically equivalent to what you would see when running the same code on the real machine.

The playground has a dozen examples preloaded. There’s Conway’s Game of Life, dimension walks, LFSR scrolling columns, parallel Gaussian blurs, and examples of hypercube communications. Load one, hit run, and you’ll understand what StarC does faster than reading any specification.

StarC Identity

The name StarC is obviously inspired by the Connection Machine’s C* language. I got the starc-lang.org domain for cheap, and as a name for a language it’s good enough. The real inspiration was me going to a yakitori place on 8th and Clement in SF, right across the street from the Star of the Sea church. Stella Maris, the patron of sailors. Inside, there’s a shrine to the first millennial saint, the patron saint of programmers. I have ‘programmers’ and a concept of ‘sailors navigating the sea of a hypercube matrix’ all in one concept. You can’t turn down that kind of associative relationship. Cray has Chapel, I have a church.

But the StarC / Catholic iconography / sailor stuff is too good to ignore. I can do some cool Catholic iconography, or nautical imagery for the visual design of this language. I settled on a nautical star for the logo because of the relationship between sailors and the Star of the Sea church. With extra gradients in the art because I’m going for early 90s maximalism. The O’Reilly book should have a seahorse on the cover, because that’s how this specific Catholic iconography extends to the Animalia.

Get StarC

The full specification, with worked examples, the StarC Playground where you can run your own StarC programs on a virtual Thinkin Machine, and the links to the Python preprocessor with instruction on how to generate real C code can be found through the StarC website.

Calculating & Performance

Quantum Chromodynamics

G. Peter Lepage, “Lattice QCD for Novices,

Bitonic Sort

Neeural Network

Performance Vs. i7-12700K | RTX 5080

One More Thing

When I began this project, I imagined I’d be building an array of four thousand tiny ten-cent microcontrollers. These plans changed slightly as I worked through the architecture of the machine, and I eventually landed on a RISC-V and FPGA combo as the nodes in this massive machine. There are definite benefits to using these chips. They’re faster, they can do floating point arithmetic, they have more memory, and they’re the key to the TDMA messaging scheme I came up with.

But I’m really only using that FPGA portion of the chip as the communications interface for each chip. An FPGA can be anything. What if I used it to implement more processors?

The original Connection Machine CM-1 used 65,536 individual processors, and my machine uses 4,096. That’s a 16x difference. By implementing sixteen small cores in the FPGA of each node, I could extend my machine to match the number of processors in the original Connection Machine.

It’s a great idea. Because of how hypercubes partition, the sixteen new processors in each FPGA only need to talk to each other. The existing backplane handles everything between physical chips. And the original Connection Machine used very, very simple processors as the nodes – they could only process one bit at a time, and not many instructions were supported. It’s brilliant. Doing this, I’d have an exact reproduction of the original Connection Machine. It could have the original specification for each processor, and it could run the same code as the original. I could have the only working Connection Machine on the planet.

So that’s what I did.

Emulating the CM-1 on 4096 FPGAs

After reading Hillis’ thesis, we get a pretty clear picture of what the individual nodes in the CM-1 actually are:

- 1-bit datapath (bit-serial)

- 8 general-purpose flags + 8 special-purpose flags

- 4K bits of external memory (12-bit address)

- One instruction: read 2 memory bits + 1 flag, apply arbitrary 3-input boolean function (specified by 8-bit truth table), write 1 bit to memory + 1 bit to flag

- Conditionalization: execute or skip based on any flag

The 16 processors per chip in the original CM-1 were connected in a 4×4 NEWS grid AND via a daisy-chain. The 16 soft-cores per AG32 should form a 4D sub-hypercube (dimensions 0-3), with the physical AG32-to-AG32 connections handling dimensions 4-11.

All of this is covered in the CM-1 implementation page.

My “emulation” or “reimplementation” of the CM-1 – I’m not sure exactly what this is – has 65,536 1-bit processors all connected as a hypercube. The architecture is a bit different because the CM-1 used routers to pass messages around to the nodes, and I’m using a weird TDMA scheme so that each node is its own router. But still, this is the closest thing to a working connection machine that’s existed in the past two decades.

Theoretically, this machine could run original code for the Connection Machine. Maybe it could. I don’t actually know, because I can’t find any original CM-1 code. But if Danny wants to meet me for a beer at Interval, I would love to talk to him about this.

Contextualizing the build

This project was insane, probably due to the mental space I was in while building it. Desperate soil yields desperate fruit, or something like that. This project began on month five of a 2-year long streak of unemployment, and if you’ve never been in that situation, I can’t convey how mentally taxing it is. Every day, for a few hours in the morning, I’d cruise LinkedIn, put in a few applications, and then spend the rest of my time working on this machine.

I got a few callbacks. Once every two months I’d have a company interested in me, have a second call, a third call, an interview with the team, and everything seems to go well. They like me. They call my references. My references say they like me. Then nothing. I thought about getting a Ouija board just so I can get some feedback.

Months of that - years of that - will tear you down. You become nothing. You are not useful. You are a burden to everyone else.

This project was my escape. Here, at least, I had some control. I could write some firmware for passing messages along the edges of a hypercube and at least I had some feedback because I have a logic analyzer on my desk. I’m serious when I say that were it not for this machine, I would not be here.

In previous roles that were heavily dependent on the engineering output of rogue garage tinkerers, I came up with the Bob Vila hypothesis. The idea goes something like this: In the mid-90s, someone asked Bob Vila why This Old House became a mainstay of public television. His answer? It was a recession. During the recession of the late 70s, people simply couldn’t afford to fix up old Victorians in Boston, so they did it themselves. They needed someone to show them how to remodel a kitchen, and which walls not to take out when renovating a room.

This theory can be extended to the incredible rise of amateur EE and MechE, with Arduinos and 3D printers and Maker Faires that coincided with the 2008 financial crisis. The dot com bubble had some really great software work despite Java. Going even further back Hewlett Packard was founded at the tail end of the depression.

So that’s the material conditions that led to me building this. It exists because of the environment that surrounds it. Not to distance myself too much from the work, but I really didn’t build this, I was just the conduit through which it was created. This is true for a lot of things; everything is a product of the environment it was created in.

This is how everything gets made. Take, for example, mid-century modern furniture. Eames chairs and molded plywood end tables were only possible after the development of phenolic resins during World War II. Without those, the plywood would delaminate. Technology enabled bending plywood, which enabled mid-century modern furniture. This was even noticed in the New York Times during one of the first Eames’ exhibitions, with the headline, “War-Time Developed Techniques of Construction Demonstrated at Modern Museum”.

In fashion, there was an explosion of colors in the 1860s, brought about purely from the development of aniline dyes in 1856. Now you could have purple without tens of thousands of sea snails. McMansions, with their disastrous roof lines, came about only a few years after the nail plates and pre-fabbed roof trusses; those roofs would be uneconomical with hand-cut rafters and skilled carpenters. Raymond Loewy created Streamline Moderne because modern welding processes became practically possible in the 1920s and 30s. The Mannesmann seamless tube process was invented in 1885, leading to steel framed bicycles very quickly and once the process was inexpensive enough, applied to the Wassily chair, a Bauhaus masterpiece, in 1925.