TDMA Routing on a Hypercube

Somehow, I invented a better connection machine.

My Thinkin’ Machine has 4,096 processors arranged at the vertices of a 12-dimensional hypercube. Each processor connects to 12 neighbors. There are no dedicated routers. Messages traverse the network using a time-division multiple access (TDMA) scheme. This message passing scheme has several interesting properties that turn my machine into something interesting:

- Deterministic link ownership (no collisions on a link, ever)

- Dimension-ordered routing baked into time (deadlock-avoidance and routing simplicity fall out)

- Bounded latency that’s a function of the superframe length (24 phases) and phase duration (the entire machine is synchronous)

This page explains how.

The Problem

Nodes must pass messages to each other, but the naive way of doing this – blasting out data and hoping everything works – has significant drawbacks. Consider the constraints:

- 4,096 nodes, each with 12 single-wire, half-duplex links to neighbors

- No dedicated router hardware routing logic runs on the node processors themselves

- Single wire connection links between nodes are a single wire, open drain.

- Single hardware UART per node must be remapped to different pins for different dimensions

- No collision detection or backoff the links can’t do CSMA elegantly

The original Connection Machine CM-1 solved this with dedicated routing silicon. This was an exceptionally difficult problem because Thinking Machines had to pull a Nobel laureate in Physics out of retirement to get these routers to actually work. I do not have the luxury of building custom ASICs for this project; I’m building it with microcontrollers that cost less than a dollar.

The Insight

In a hypercube, each node’s address is a binary number. Node 0x2A3 is connected to every node that differs by exactly one bit: 0x2A2 (bit 0), 0x2A1 (bit 1), 0x2AB (bit 3), and so on. To route a message from source $S$ to destination $D$, XOR the addresses:

The set bits in $\Delta$ tell you which dimensions to traverse. If bit 7 is set, the message must cross dimension 7 at some point. The number of set bits equals the number of hops.

If you traverse dimensions in a fixed order, always dimension 0 before dimension 1 before dimension 2, and so on, you get deadlock-free routing for free. This is dimension-ordered routing, and it’s a known result in the literature (see Bertsekas 1991).

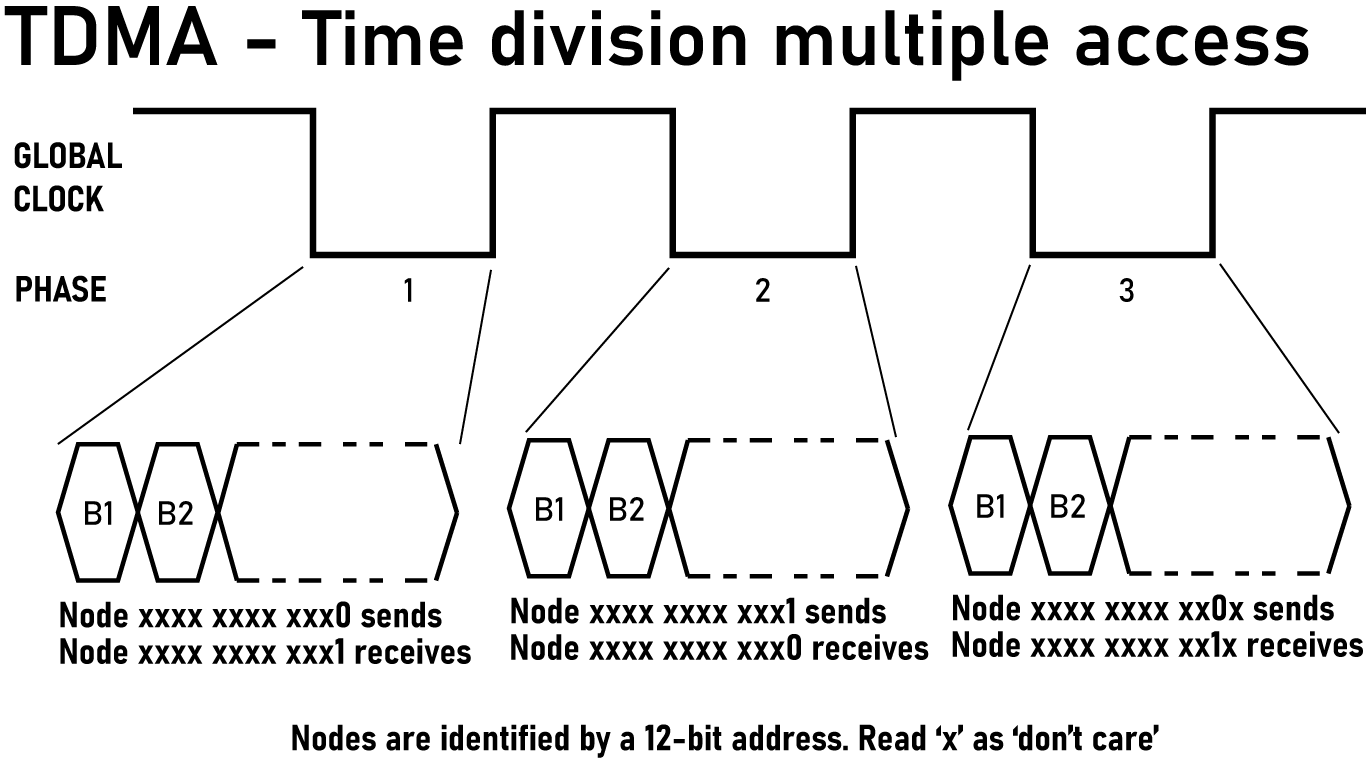

Divide that clock into $2n$ phases, where $n$ is the number of dimensions. Phase $2d$ activates dimension $d$ in the low→high direction; phase $2d+1$ activates the same dimension in the high→low direction.

Now collapse this back to hardware. We have a (slowish) global clock. Each chip has an binary address. On clock phase $2d$, if that chips address bit $d$ is $0$, we map the pin for dimension $d$ connections to the hypercube UART transmit. On clock phase $2x+1$, and if that chips address bit $d$ is $1$, we map the pin for dimension $d$ connections to the UART receive.

We multiplex the UART for each chips hypercube connections through time. That’s it, that’s the entire trick. This requires a few things:

- A slow global clock, on the order of 1 to 10kHz. This is fairly easy even in a large machine because dealing with a 1kHz clock is a piece of cake.

- A microcontroller where UART peripherals can be remapped to any pin. This is difficult, but there are chips that can do it.

- Optionally, and to make things very easy, a second ‘sync’ clock that ensures the phase number is the same on all chips.

The Phase Schedule

A single communication cycle consists of 24 phases:

| Phase | Dimension | Direction | Transmitting Nodes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0→1 | Nodes where bit 0 = 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1→0 | Nodes where bit 0 = 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 0→1 | Nodes where bit 1 = 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1→0 | Nodes where bit 1 = 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 0→1 | Nodes where bit 2 = 0 |

| 5 | 2 | 1→0 | Nodes where bit 2 = 1 |

| … | … | … | … |

| 22 | 11 | 0→1 | Nodes where bit 11 = 0 |

| 23 | 11 | 1→0 | Nodes where bit 11 = 1 |

In phase $2d$, nodes with address bit $d = 0$ transmit to their neighbor in dimension $d$. In phase $2d + 1$, nodes with address bit $d = 1$ transmit. Every link is active exactly twice per cycle — once in each direction — and there is never contention for a link.

Dimension-Ordered Routing

Given source $S$ and destination $D$, compute $\Delta = S \oplus D$. The message traverses dimensions in order, using the appropriate phase for each hop.

For each dimension $d$ from 0 to 11:

- If bit $d$ of $\Delta$ is not set, skip this dimension

- If bit $d$ of the current address is 0, transmit in phase $2d$

- If bit $d$ of the current address is 1, transmit in phase $2d + 1$

Because dimensions are traversed in order and phases are ordered by dimension, the sequence of phases used is always monotonically increasing. A message never waits for a phase to “come around again.”

Worked Example & Bounded Latency

An Average-Case Routing Task: Route a message from node 0x2A3 (binary 0010 1010 0011) to node 0x91C (binary 1001 0001 1100).

The set bits are: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11. That’s 9 hops.

| Hop | Current Node | Dimension | Current Bit | Phase | Next Node |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0x2A3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0x2A2 |

| 2 | 0x2A2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0x2A0 |

| 3 | 0x2A0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0x2A4 |

| 4 | 0x2A4 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0x2AC |

| 5 | 0x2AC | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0x2BC |

| 6 | 0x2BC | 5 | 1 | 11 | 0x29C |

| 7 | 0x29C | 8 | 0 | 16 | 0x19C |

| 8 | 0x19C | 9 | 1 | 19 | 0x11C |

| 9 | 0x11C | 11 | 0 | 22 | 0x91C |

Phase sequence: 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 11, 16, 19, 22. Strictly increasing. Message delivered in one cycle.

Worst-Case Routing: Route a message from node 0xFFF (binary 1111 1111 1111) to node 0x000 (binary 0000 0000 000). This is the maximum possible Hamming distance on a 12-bit address space. Every bit differs.

Because the source starts with all bits = 1, every hop uses the odd phase for that dimension (the 1→0 direction): phase $2d+1$.

| Hop | Current Node | Dimension | Current Bit | Phase | Next Node |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0xFFF | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0xFFE |

| 2 | 0xFFE | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0xFFC |

| 3 | 0xFFC | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0xFF8 |

| 4 | 0xFF8 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 0xFF0 |

| 5 | 0xFF0 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 0xFE0 |

| 6 | 0xFE0 | 5 | 1 | 11 | 0xFC0 |

| 7 | 0xFC0 | 6 | 1 | 13 | 0xF80 |

| 8 | 0xF80 | 7 | 1 | 15 | 0xF00 |

| 9 | 0xF00 | 8 | 1 | 17 | 0xE00 |

| 10 | 0xE00 | 9 | 1 | 19 | 0xC00 |

| 11 | 0xC00 | 10 | 1 | 21 | 0x800 |

| 12 | 0x800 | 11 | 1 | 23 | 0x000 |

Phase sequence: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23. Strictly increasing. Message delivered in one cycle.

Now route the opposite direction from node 0x000 (binary 0000 0000 000) to node 0xFFF (binary 1111 1111 1111).

Because the source starts with all bits = 0, every hop uses the even phase for that dimension (the 0→1 direction): phase $2d$.

| Hop | Current Node | Dimension | Current Bit | Phase | Next Node |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0x000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0x001 |

| 2 | 0x001 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0x003 |

| 3 | 0x003 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0x007 |

| 4 | 0x007 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0x00F |

| 5 | 0x00F | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0x01F |

| 6 | 0x01F | 5 | 0 | 10 | 0x03F |

| 7 | 0x03F | 6 | 0 | 12 | 0x07F |

| 8 | 0x07F | 7 | 0 | 14 | 0x0FF |

| 9 | 0x0FF | 8 | 0 | 16 | 0x1FF |

| 10 | 0x1FF | 9 | 0 | 18 | 0x3FF |

| 11 | 0x3FF | 10 | 0 | 20 | 0x7FF |

| 12 | 0x7FF | 11 | 0 | 22 | 0xFFF |

Phase sequence: 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22. Strictly increasing. Message delivered in one cycle.

Bounded Latency

The maximum number of hops in a 12-dimensional hypercube is 12 (all bits differ). The maximum number of phases is 24. Every message — regardless of source, destination, or network load — completes within one 24-phase cycle. This isn’t worst-case latency, it’s the latency for every possible message between every possible pairs of nodes in the hypercube.

Wall-clock latency depends on phase duration:

| Phase Rate | Phase Duration | Cycle Duration | 12-Hop Latency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 kHz | 1 ms | 24 ms | 24 ms |

| 10 kHz | 100 µs | 2.4 ms | 2.4 ms |

| 100 kHz | 10 µs | 240 µs | 240 µs |

At 10 kHz phase rate with 1 Mbps baud, each phase carries ~100 bits — enough for a 10-byte payload plus header. The entire machine can exchange data at 2+ Gbps aggregate bandwidth with deterministic 2.4 ms latency.

What Falls Out

The Connection Machine was famous beyond its blinkenlights for what fell out of the architecture. A bitonic sort algorithm is perfect for hypercube clusters of computers. Using the NEWS grid of the Connection Machine, intelligence services had the fastest image processing machine on the planet. This TDMA scheme is the same thing; really cool stuff just falls out of the architecture:

No collision detection. Two nodes never try to transmit on the same link simultaneously.

No backoff or retries. Collisions don’t happen, so recovery logic doesn’t exist.

No buffering beyond one message. A node receives at most one message per link per phase. The “buffer” is a single register.

No deadlock. Dimension-ordered routing is provably deadlock-free, and the phase schedule enforces dimension ordering automatically.

Trivial routing logic. The algorithm at each node:

void route_message(uint16_t dest, uint8_t *payload) {

uint16_t delta = my_addr ^ dest;

for (int dim = 0; dim < 12; dim++) {

if (delta & (1 << dim)) {

int phase = 2 * dim + ((my_addr >> dim) & 1);

wait_for_phase(phase);

transmit(dim, payload);

return; // next hop handles remaining dimensions

}

}

}

That’s it. The complexity is in the schedule, not the silicon.

Why This Works Here

This scheme exists because of constraints. The project couldn’t afford dedicated router ASICs. I couldn’t find a microcontroller with 12 hardware UARTs. The one UART I had could be remapped to different pins at runtime. TDMA solves all of these problems simultaneously. One UART handles all 12 dimensions because we’re only using one dimension at a time. There’s no router hardware because the TDMA schedule is the router.

The original Connection Machine CM-1 used dedicated routing hardware because the constraints were different: custom silicon, DARPA budget, and a goal of supporting arbitrary asynchronous communication patterns. The routers were complex because they were solving the general case. My workloads are synchronous. Compute, exchange, compute, exchange. For that pattern, the general case is unnecessary overhead. Lockstep TDMA is a feature, not a limitation.

There is one gigantic, glaring problem with this idea. A naive interpretation of this routing scheme would complain that I just reduced the potential speed of the machine by a factor of 24. This is true, but it’s lacking context. This paper from NASA Ames in 1990 assessed the Connection Machine from a programming standpoint, and the takeaway is not good.

The NASA assessment of the Connection Machine says, “irregular communication through the router is very expensive and should be sparingly used.” Also, _“The router is the key to the CM. The current machine has a router that runs at roughly 1% of floating point speed. This makes router-intensive algorithms unattractive in terms of their performance.”

The CM-1’s general purpose router, the thing that made it flexible, was so slow that NASA’s assessment was basically, “don’t use it”. The machine could route messages arbitrarily and asynchronously but in practice nobody used it because it was a hundred times slower than compute.

The TDMA scheme gives up the theoretical capability of arbitrary asynchronous routing, but that was unusable to begin with. In exchange, I get structured communication that I can actually use every cycle.

My Context

This sounds smart, and it probably is, but I must admit I’m a bit out of my depth here. Not so much in that I couldn’t think of how to do this, but my depth doesn’t extend to why this wasn’t done before. I’ve checked the literature, and the ideas are there. Bertsekas goes through the dimension ordering of message passing through a hypercube, and Stout sort of, kind of, applies this ‘master scheduler clock scheme’. Kopetz says, ‘yeah man, just divide the communication up by time’. No one put these two ideas together to create a collision-free hypercube with bounded latency.

The original Connection Machine CM-1 solved a slightly different problem with its routers. The CM-1 solved general purposes communication under unpredictable traffic. This required buffers, arbitration, and deadlock avoidance. In the CM-1, there is a lot of silicon dedicated to simply passing messages between nodes.

This TDMA scheme requires effectively zero silicon, and only needs a relatively slow global clock. I lose the idea that ‘any node can talk to any dimension at any time’, but if you zoom out to the superset of the phase clock that doesn’t really matter at all. It’s just a small implementation detail.

Am I the first person to think of this? I have no idea.

References

-

D. P. Bertsekas et al., “Optimal Communication Algorithms for Hypercubes,” Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 1991. PDF

-

Q. F. Stout, “Intensive Hypercube Communication: Prearranged Communication in Link-Bound Machines,” Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 1990. Abstract

-

Kopetz, H., & Grünsteidl, G. (1994). “TTP—A Protocol for Fault-Tolerant Real-Time Systems.” IEEE Computer, 27(1), 14–23. PDF

-

Robert Schreiber, “An Assessment of the Connection Machine,” RIACS Technical Report 90.40 (June 1990) PDF